It’s annoying. Since one of my interests is in metaphysics and its implications, it annoys me when people offer a metaphysical hypothesis without doing the hard work of systematics. One reason it annoys me is that, from my background as a design engineer, designs have to work. Another more important reason is that worldviews matter, and sloppy formulations can have a deleterious impact on people’s lives.

Except for a two-year stint to study theology, biblical studies, etc., at a Lutheran seminary, I worked for some 40 years as a design engineer. I even received 15 US patents for my inventions. I mention that only to suggest that I know something about design.

The cardinal principle in design engineering is that the design has to work. This means it has to meet the specifications. If it doesn’t, a design engineer may have a short career, or even people could get hurt. Specifications for systems are often very complex. They include not only the final function but also cost, materials, time frames, production factors, deployment, the functional environment, repair ease, fault detection, and so on. Some of the systems I worked on in the aerospace industry had many pages of specifications.

What it takes

So, what does it take to design something that works? Of course, it takes knowledge and imagination. That requires training, study, and experience. But here I want to talk about why a systematic approach is crucial. Machines, software, and other systems are complicated. They usually have many moving parts that are interrelated. The human body is a good analogy. There are various organs that perform a function, but they are also related to other functions and are integrated into a whole we call a human organism. The various components don’t stand alone. Other factors within the organism impinge on their function as well.

So, what might this have to do with a sound metaphysics? It’s crucial. One has only to survey the literature of prominent metaphysical systems in history to see that they are complex and expansive. For them, it’s not enough to make some cursory assertion and leave it at that. No. They have to deal with all sorts of implications in how parts of a system are interrelated and affect each other. In other words, each assertion affects what follows. As an example in machine design, each step in the design constrains what is possible going forward. A simple example is that if you take up too much space for some component, then the rest has to be smaller to meet the overall size specification. That may not be adequate for its function. This also applies to materials, power factors, stresses, environments, cost, range of motion, and on and on. So, in designs, there has to be a lot of forward-looking for what comes after. This is systematics — evaluating the implications of each part as it relates to the whole, with the specification in mind.

Metaphysics

What I see consistently from both many academics and social media influencers is laziness or avoidance of systematics. They just make some narrow assertion and leave it at that. It may sound good and be appealing, but if tough questions are asked of it (not often), it can collapse or devolve into all sorts of ridiculous contrivances. Hence my annoyance. Ideas matter.

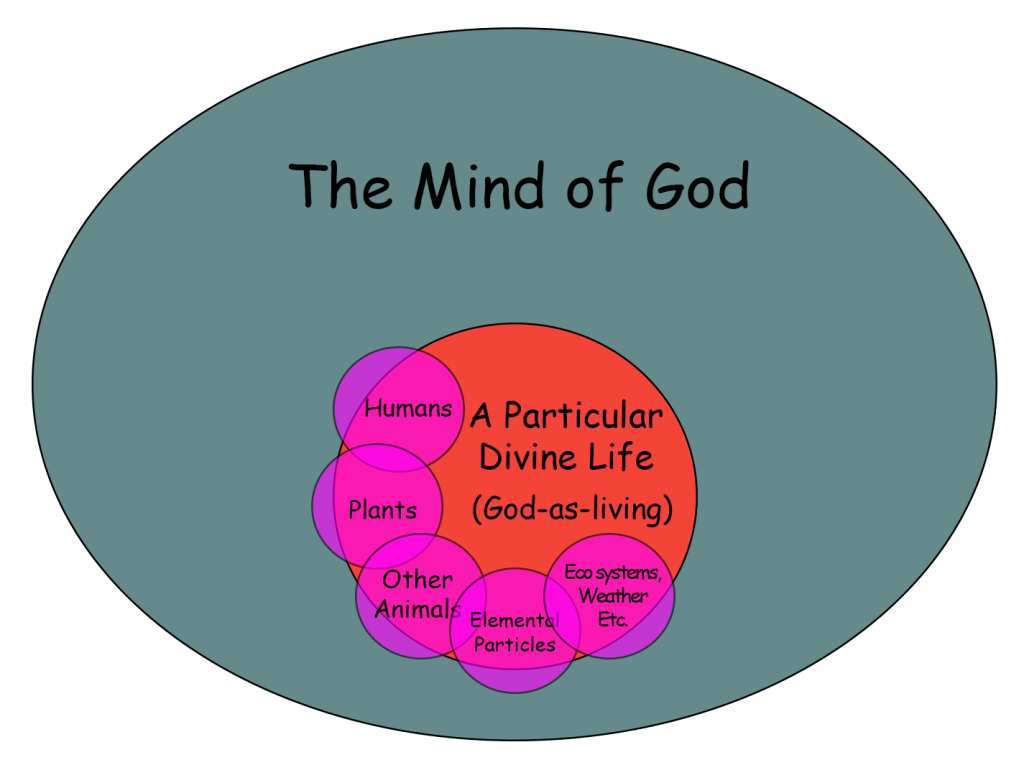

The essence of systematics in metaphysics is dealing with all the issues at roughly the same time. Now, it’s not necessarily a linear process, but thinking about the effects on other factors in the system can short-circuit a lot of false starts. For instance, in theology or religious philosophy, ontology (about being) is a bedrock from which many things depend. But ontology doesn’t just spring forth from nothing. It is formulated based on prior suppositions, often based on intuitions about reality. For instance, does ontological dualism seem OK or not? Does there seem to be meaning and purpose fundamental for this reality? Is there free will? Is this reality fundamentally flawed or not? Ontologies usually spring forth from both rational, empirical, and intuitional factors. Here again, this is systematics. Lots of factors go into a metaphysical formulation. Each assertion affects what can follow.

Now, if the basic intuition for a metaphysic is that reality is fundamentally non-intentional, the system can be relatively simple. Things just happen for no grand reason. It’s all autonomic. Full stop. Of course, this rarely ends there. That’s because most people have the intuition that there is some sort of libertarian free will and that there are objective values (moral realism). This is the fly in the ointment. Again, so we get contrivances that inevitably don’t work.

However, when it comes to intentional formulations, particularly theism, things get complicated very fast. From that intuition, a vast number of formulations have emerged over the centuries and continue today.

The Key

Now, I wouldn’t presume there is a definitive theistic formulation (even my own) that has no problems. That’s not how finite systems work. Speculations about the fundamental nature of reality are always limited by our knowledge, creaturely strengths and weaknesses, biases, provincial and species inclinations, etc. However, at the very least, we should strive to be comprehensive (systematic) in our efforts. This means not shying away from the complete and difficult questions and issues.

For the theistic system I developed, I have criteria that I think are essential. Others may have different ones. Fine. Mine are the product of logic, empiricism, and experience that in some cases, lead to an intuition (a gestalt) about reality. Here are the criteria I chose.

- Have verisimilitude (appears to be true)

- Be monistic

- Be ontologically personal

- Be reasonable

- Be systematic

- Be science-friendly

- No violational supernaturalism

- No eschatology (end times) or soteriology (salvation schemes)

- Be world-affirming

- Affirm religious experiences and intuitions

- Affirm ongoing divine activity

- Affirm teleology (personal and divine purpose)

- Affirm objective meaning

- Affirm objective value (moral realism)

- Affirm free will

- Affirm the efficacy of prayer

- Better address the problem of evil

- Address consciousness

So, for me, all these factors need to be adequately addressed in the theology, and the answers offered need to be systematically sound and consistent.

Is it too much to ask for others to be systematic before they assert something? Sure, they can pick their own important factors in the system and present arguments for them, but don’t just spout some simple assertion and not address the profound implications of that, taking everything into account.