“The two most important days in your life are the day you were born and the day you find out why.”

Mark Twain

“The two most important days in your life are the day you were born and the day you find out why.”

Mark Twain

When we hear others talk about a worldview that is oppositional to ours, whether it be theism, non-theism, atheism, or something else it can be tempting to have a negative view of them as a person. Here I’m not talking about a valid criticism of their positions. That’s legitimate. Opposing worldviews can be existentially threatening and engender this disparaging attitude.

However, if we understand that they too are a finite manifestation of God – an incarnation, that changes things. It means that like us they are participating in the struggle to make sense of themselves, understand their place in reality, and its meaning. Also like us, they have their own particular make-up, dispositions, histories, and cultures in which they find themselves. If we view others this way we can also understand that we too are flawed and, to a large extent, the product of our own particular situation. Then, we can engage with others in a spirit of humility and solidarity in this grand narrative of what it means to live.

One of the guiding principles I have adopted for developing a theology is minimalism. Metaphysical speculations should be kept to a minimum and only arise where they are needed to offer answers to pressing existential questions and are actionable in life. Accordingly, with respect to the topic of an afterlife, I don’t have much to say. However, most people are concerned about the question, so I think it should be addressed as best it can be within the minimalist constraints.

There are all sorts of speculations in religion and philosophy about what happens after death. They range from a dissolution of the self within the ultimate to having some sort of “existence” beyond. That existence could be non-corporeal (a spiritual being), a heavenly existence, a rebirth to another life (reincarnation), or some other formulation.

What I can say, coming from the ontology of a divine idealism is that even after our earthly life ends, the memory of us and our life is eternal in the Mind of God. What God decides to do with that memory could take many forms. This is where all I can offer are some possible options that come to mind. There could be many others.

It is important to remember that all these options are just metaphors. The true reality of things could be very different.

That’s about all I would be willing to speculate about. But here’s the thing. I firmly believe that God loves each and every person and creature. If we believe that, then we can also believe that God will act in a loving way toward each life. Personally, I think that is enough.

The term incarnation derives from the Latin verb ‘incarno’, which itself is derived from the prefix ‘in’- and ‘caro’, “flesh”, meaning “to make into flesh” or, in the passive, “to be made flesh”. This term is prominent in Christian theology but the idea of a god “becoming flesh” is nothing new. In fact, in one of the earliest ancient texts — The Epic of Gilgamesh (circa 2100 BCE), Gilgamesh is 1/3 human and 2/3 god. Besides Christianity, it also shows up with the avatars in Hinduism and in Greek mythology where a god takes on human form.

The fundament issue that has prompted the incarnation idea is the perennial question of “the One and the Many”. This question is not surprising because as humans we have a sense of individuality but also see ourselves as participating in something greater.

Now, there are different concepts of how the One and Many are related. One model is dualism. This model arose significantly during the axial age with the emergence of the monotheistic religions of Christianity and Islam. It says there is a stark ontological otherness of the divine and the world. Zoroastrianism, which had considerable influence, is a prime example of this dualism. In this model, God is wholly other from this world.

There are well-known problems with forms of dualism. Theologically, it presents problems of interaction and intervention between God and the world. Philosophically there is an interaction problem represented by the mind/body issue. I won’t discuss dualism in depth here because I want to suggest an alternative — monism.

Monism

In monism, there is only the One but there are distinctions to be made within the One. Those distinctions represent the Many. So, how are the distinctions characterized? This can vary within metaphysical systems, but I describe a distinction as an ‘aspect’ of the One. An aspect is both a part of something and a unique perspective. These ‘aspects’ could also be thought of as incarnations (the ultimate becoming finite). This “becoming finite” is represented by the Greek word, ‘kenosis’ and shows up in various wisdom literatures including Christianity. Kenosis means the act of emptying or self-emptying.

There are similar characterizations of this type of monism in various metaphysical systems. As an example, in a popular form of Hinduism, Vishishtadvaita Vedanta the term used is ‘qualified’ in qualified monism. Brahman is the One but the Many are real manifestations of the One. In the West, it also shows up in some forms of panentheism. A common metaphor for this is “The world is the body of God”.

Here are some Venn diagram metaphors that illustrate this (a priority monism) and the Divine Life Communion extensions of that ontology (about being).

If this ontology is entertained, there are some very significant implications.

Personally, it means you are an incarnation — a finite manifestation of God in this reality. Since the theology offered here is a thoroughgoing panentheism, there is both a transcendent nature of God and a living nature. Accordingly, I call these incarnations, God-as-living.

As an incarnation, there are several intrinsic features of your being.

First, you have a transcendent divine depth within you. Although you are finite, you also participate in God-as-transcendent. This means you do have access to divine revelation. Now, as finite creatures, this revelation often presents itself in ambiguity. This is why we must constantly challenge ourselves and our beliefs and be humble about our positions.

Second, it means you inherit a finite share of transcendent divine freedom. There are obviously constraints inherent in a finite life, but within those constraints, you do have freedom of choice.

And third, you are loved and eternal within God. Metaphorically, just as a parent loves their child, God-as-transcendent loves each incarnation. This means you are never alone, no matter what the trial is you may be going through. This also has implications regarding the afterlife. I talk about this in my essay on “After Life“.

There is much more to say about all this and that is covered in the various essays on the website.

Today I’m going to psychologize a bit concerning the formulation and evaluation of worldviews and metaphysical systems. In 1994, I read the book “Descartes’ Error” by neurologist António Damásio. It was a game-changer for me. At the time, I subscribed to a common notion that emotions could be the bane of being rational. Both Plato and Aristotle felt that reason was superior to emotions or as they called them, the passions. The idea is that emotions can taint reason. This view is understandable because who hasn’t seen either in themselves or others where emotions can lead to unreasonable conclusions? I felt the same way. However, that view changed after I read Damasio’s book. There were similar books like Joseph Ledoux’s “The Emotional Brain”.

What Damasio and others showed was that emotions aren’t just some independent force tainting reason but actually an intrinsic and necessary part of reason. In his book, he talks about several real-life examples of what is going on. These examples illustrate what happens when the parts of the brain associated with emotions become damaged. A famous example of this Phineas Gage. Gage was a construction foreman who was installing an explosive charge into a hole in a rock. An accidental spark ignited the charge and drove a tamping iron through his left eye and into his left frontal lobe. He survived that accident, but his personality was changed forever. Contrary to his previous personality, he became volatile and profane with poor judgment and the inability to take on complex tasks.

An even more striking example Damasio recounts is a man who by all accounts was a perfectly reasonable, rational individual, well known for his judgment in complex issues. This man, however, sustained a lesion in an area of the brain known to be responsible for emotions. While not life-threatening, this damage had a lasting effect on the man. His psychological affect (emotions) became subdued. Also, whereas before his judgment was unassailable, after the disease that changed dramatically. He was able to reason just as well as before but unable to make good judgment calls. He had great difficulty in making decisions and as a result, his judgments were suspect. Something was missing. That missing component seems to be emotion.

What are we to make of these examples? What Damasio and others claim is that emotions are a critical element in making judgments. They are not necessarily a taint on making well-reasoned judgments but instead are crucial for them.

So, what’s going on with the process of reason? There is obviously a strong element of logic involved. The structure of logic creates guard rails within which the process can proceed, avoiding wild unsustainable threads of thought. However, logic is not some sterile, simple process. Logic requires language and language is inherently value-laden. Each step in reasoning has a value associated with it. In a simple case, this valuation is embedded in subscribing to things like the law of noncontradiction or the excluded middle. It can also be encoded in a list of logical fallacies. These are all value-laden because there is a sense of wrongness (a value) to them. In other words, emotions are in large part about valuations. The reason emotions manifest themselves in physiological ways (feeling good, being anxious, rapid heartbeat, sweating, feeling calm) is because there are deep-seated values at work.

This value may not be something simple but rather a combination of many factors. However, even with its complexity, in the gestalt (holism), it offers a weighting force. It pushes the reasoning in certain directions.

Emotional Commitments

As life proceeds from childhood, various emotions are imbued within us. These proceed from both positive and negative experiences. Early on, pleasure and pain play a pivotal role in the valuations we make about circumstances and our response to them. As we get older, our valuations become more complex and nuanced. Still, these emotional (valuational) responses shape how we will evaluate what is presented to us and influence our response. There are what I’ll call “emotional commitments”. A commitment is a strong bias toward something. However, all commitments have an emotional content. That’s because there is always some value associated with it. These commitments are deeply engrained within us and almost autonomic. One might call these “knee-jerk” responses just like those tested in the doctor’s office. This can be advantageous because we can make very fast decisions. It can be valuable in certain circumstances but also problematic if those biases are counterproductive. The point is that we all have emotional commitments toward a certain perspective of reality. Those commitments shape how we will evaluate new experiences and information as it arrives. Depending on what those commitments are it can create either a blockage or openness to the new we experience and what it entails.

Metaphysical Emotional Commitments

Is there any doubt that there are strong emotional commitments in metaphysical worldviews? One has only to witness the heated arguments among opposing worldviews. Metaphysics speaks to “beyond or underlying the physics”. Since the foundations of reality are underdetermined by our knowledge and perspective, metaphysics speculates about the unknown and what it might mean. As such, there are existential concerns (life, death, meaning, freedom, value, etc.) in the balance. These concerns reflect our sense of self and the meaning of our lives. No wonder there are emotions involved.

For millennia there have been many metaphysical formulations offered. They try to offer a picture of reality that addresses not only what empirical investigations suggest but also existential concerns (what we care about deeply). For those interested in creating or evaluating metaphysical systems, I think emotional commitments should be considered. What might those be?

Emotional commitments are as complex as individuals. They stem from the entire history of the individual as well as their engrained makeup, be it genetic or cultural. As psychology has shown, they may even be a mystery to the individual, buried within the unconscious mind. However, if an effort is made, they can become somewhat apparent if probed. If that task is undertaken, perhaps it can inform future choices.

At this point, I think it is also important to understand that there is a hierarchy and interaction of these emotional commitments. Some provide more force than others. There can be competition among them. They each have a certain weight in the evaluative process. This can create what psychologists call a cognitive dissonance. I offer a metaphysical metaphor about this here. As the mental process proceeds, inevitably the strongest emotional commitments will have a strong influence on the result, often tipping the balance.

Also, another factor could be called the domino effect. In this effect, if one particular domino (say a proposition) falls then many subsequent dominos will fall as well. There is an entailment of ideas. This can be rapidly assessed in our minds. If this happens the emotional response can be multiplied enormously. Each domino represents some emotional commitment.

Here, I’ll offer an example within religious thought, but it can apply, as well, to other metaphysical worldviews. Religious philosophers, theologians, and adherents are a varied bunch. They each have their own histories and personality types. They also have their particular emotional commitments. What might those be? There is a continuum for these commitments.

For some, there is a strong emotional commitment to certainty. We see this with evangelical theologians and adherents. It is very important to them to have a sense of certainty regarding the worldview that ensues from the philosophy or theology. For some, this means a commitment to the inerrancy of some scripture or religious text. If that domino were to fall the subsequent falling of other dominos may be more than they could emotionally bear.

At the other end of the continuum, there are religious thinkers and adherents who aren’t that concerned about certainty, and no matter how incoherent ideas may be, they are perfectly willing to accept them.

In between is where we find most of these religious thinkers. There is a commitment to rigor but also an acceptance of some level of uncertainty. They recognize that metaphysics is speculative and underdetermined.

Since we are all existential creatures, this same emotional dynamic applies across the board for any system that impinges on our existential interests. This includes metaphysical systems like atheism, theism, non-theism, agnosticism, materialism, and the like. The question to ask is what are the emotional commitments and their weighting power?

If the strongest emotional commitment is sustaining a particular worldview, that will guide what can follow and be entertained. If the strongest commitment is toward certainty, that will narrow what can even be considered. If, however, the dominant emotional commitment is to the truth, that can trump all other commitments. Obviously, that can be scary because it may mean abandoning or modifying a worldview. Not an easy task.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, creating or evaluating a metaphysical or theological system is a judgment call. However, in that process of creation or evaluation, there can also be a probing and evaluation of the personal emotional commitments that are at work. Are the commitments strongest toward the truth or are they aimed at sustaining a current position? This can be difficult to determine and requires courage to go there but if taken seriously it might result in a more stable and less conflicted state.

I’m a theist but I think salvation is a bad idea. Salvation schemes were the inevitable consequence of the world rejection that was ubiquitous during the inception period of the major world religions. This period was roughly the first millennium BCE, give or take a few centuries before and after. If this world (reality as a whole) is fundamentally flawed, there must be some “fix” available. So, salvation enters the picture. For several reasons, salvation is a bad idea. Here are some:

1. It’s based on a naïve and sentimental view about how life should be.

2. It says that humanity is intrinsically flawed and needs fixing as well.

3. It has requirements that must be met, or salvation won’t be attained. This creates the fear of losing out or even suffering negative consequences. In some situations, this can be personally damaging.

4. It can lead to unwavering dogmatism and denigration of those who have it wrong.

5. It provides the opportunity for religious institutions (and cults) to exert control over their adherents.

6. It can create a fatalism about this world that thwarts full engagement in making it a better place.

7. It creates an elite class of those who get the requirements right.

8. It casts a negative light on ultimate reality as the source of this reality and makes any fruits of that reality suspect. Theologically, God messed up. Non-theologically, whatever is the source of this reality is either indifferent, evil, or incompetent.

Instead, we can affirm this reality as it fundamentally is and fully commit to doing whatever we can to make it a more loving, beautiful, and meaningful place for all creatures.

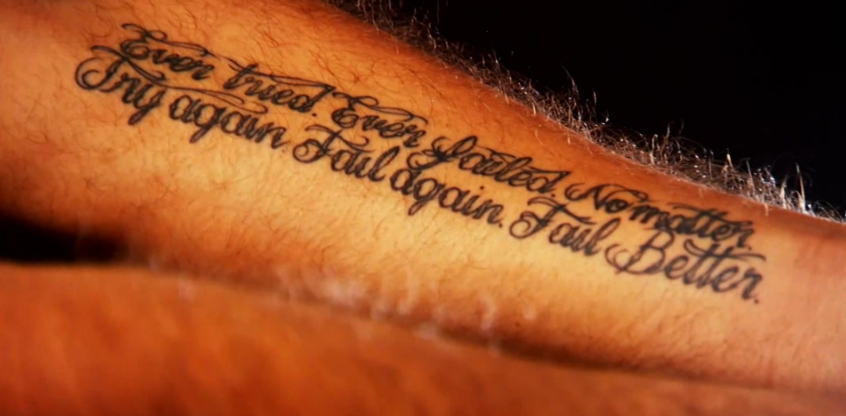

Winston Churchill defining success: “Success is the ability to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.” One of my favorite athletes is the Swiss tennis player Stan Wawrinka. He has, in my opinion, one of the best one-handed backhands of all time. It’s so powerful and beautifully done. However, the other thing I admire about him is his attitude. He’s been a top player but never dominated like the Big Three (Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic). So, how did he deal with the losses? Here’s the tattoo he put on his forearm:

It reads: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No Matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail Better.”

We are all familiar with failure. It’s just part of life. The question is how do we deal with it? These two individuals offer exemplary models. Failures test us. They may shake our confidence. It can be tempting to lose hope. But there is no upside to that. It takes courage to try again. And fail again. It takes faith in the face of doubt to keep trying. But isn’t that what really matters? Isn’t success as Churchill defined it?

Humans have had an interest in metaphysics for millennia. When did it all start? That’s hard to know but things like red ochre and personal items were even found in Neanderthal graves. That makes one wonder why. Then, of course, there is the long history of metaphysical thinking from early animism to what we have today.

Metaphysics reaches beyond what is straightforwardly apparent. That requires speculations. The human psyche needs to find some broad orientation for living. There are essential questions that beg for answers. What is the meaning of life? How should I live? What happens when I die? What is the good? And so on.

If metaphysical systems help people orient their lives, and inform how they should think about things, and live, the question is “Which one?” Lord knows there is no shortage of these systems. There are even new ones coming on the scene all the time. Not only are there religious systems but also non-religious systems. More-or-less systematic attempts date back at least three or four thousand years. If internet activity in forums and online media outlets like YouTube is an indication, there is considerable interest in metaphysical explorations.

For most people, these explorations aren’t just for fun. They are existentially (what matters to us) important. So, choosing one to orient one’s life around is also important. How does that choosing process come about? For most people, the choice was initially already made by their upbringing or the culture they found themselves in. However, for some, there comes a point when their current metaphysical system (religious or non-religious) isn’t working for them anymore. So, they may start looking for something else. The search is on. With so much metaphysical thought out there that can be a daunting task. However, I think it can be facilitated by understanding what essentials would have to be present in a system such that it is a viable option. We all have intuitions about what is important to us. Those intuitions may not be that explicit but they can be. They can be thought of as essential criteria that must be met.

Understanding the essential criteria can help short-circuit a fruitless extended evaluation. If something in the system doesn’t meet a criterion, that can be a deal-breaker. It is no longer viable. Some systems are complex. So this may require scanning ahead to look for problem areas. Addressing existential issues is difficult and often put off for much later in a system (if at all). If they aren’t addressed at all, that should be a red flag. By looking for deal-breakers that can avoid a lot of wasted time. It can help one know when to quit on that particular approach. From there, the search can move on.

Now, some proposed metaphysical systems are just in the fledgling stage but might be promising. This makes things a bit more complicated. One way to evaluate an incomplete new system (or anyone that doesn’t explicitly address existential concerns) is to look at the early fundamentals and project where they can lead. A good place to start is ontology — how things fundamentally are. Is there a monism or dualism? Is it simple or complex? Is there fundamental intentionality or non-intentionality involved in how reality becomes constituted? And so on. Initial fundamentals constrain what can follow and determine whether or not it is even possible for certain criteria to be met. It takes some experience with various systems but using this method may greatly facilitate an evaluation.

Now, at this point, it is important to describe what this evaluative process looks like. Since systems contain a lot of propositional content, it might seem that the evaluations are just utilizing the step-by-step reasoning in the cognitive processes, but that need not be the case. In fact, intuitions come into play more often than not and can be a powerful tool. While intuitions often aren’t that explicit, they can still give a sense that something seems right or is off-putting. There can be a consonance or dissonance with something deep within. I talk about that here.

While so far I’ve talked about a personal evaluation of metaphysical systems, this applies equally to those who are trying to develop one. As an example, recently I’ve seen a lot in forums and online media about the problem of consciousness (subjective experience) with many proposals being offered. Inevitably, they either propose a metaphysical system or expand on one. For developers, knowing when to quit on a certain line of thinking and try something else can avoid wasted time and crucial (perhaps terminal) problems down the road.

So, as an example, here’s the list of criteria I have used to evaluate metaphysical systems and develop my own. Obviously, answers to these criteria need to be unpacked so I’ll put in links where I do so. Your criteria may be different but if you have a sense of them, perhaps you can quickly know when to quit on a particular approach. The key here is that all the criteria must be met or at least solvable without jeopardizing the others.

Essential Criteria

Metaphysics is about questions and answers. Why is there something? Why is the world the way it is? What is the meaning of life? And so on. Some questions about reality may find straightforward answers. We can make observations and postulate reasonable explanations. However, some questions are underdetermined by observation. There can be different answers from the same observations. In that case, to formulate answers requires inferences and speculations. So, we get metaphysical systems, both religious and non-religious. These systems can vary widely. Why?

To answer that question requires a deep dive into where metaphysical systems come from and why they take the shapes they do. Obviously, that is a complex question but in this post, I want to focus on a particular feature of metaphysical systems — a value assessment of the world. That value assessment can also be complicated but it can be broadly characterized as world-affirmation or world-rejection.

Metaphysical systems don’t just pop into existence from nowhere. They emerge from worldviews. When a deep question is asked about reality, the answers are greatly influenced by the worldviews held by individuals and cultures of the time. At any particular time in history, a certain sentiment may emerge about the state of the world. When times are hard, perhaps with lots of violence and wars going on, the assessment of the world will tend to be negative. When times are good, it may be more positive. This also applies to metaphysical thinkers and their psychological makeup. Also, sometimes an event can create a psychological crisis that changes a worldview. Legend has it that Siddartha Gautama (the Buddha), who was raised in a privileged environment, when exposed to the real world with its troubles had his worldview dramatically changed. This spurred him on to develop what we now know as Buddhism. Other seminal religious thinkers have their own motivating histories.

Worldviews of most people may not be so dramatic. It can be just an inculcation from the family, group, or culture. Still, they shape how we think about the world and our place in it. When certain metaphysical questions are asked, the answers tend to flow from that worldview.

Metaphysical systems, while not totally linear, do build on foundational principles that set the tone for what can follow. A key factor in how those foundations are formulated is a world value assessment. Shortly, I’ll talk about how certain assessments (world affirmation/rejection) have had a profound effect on religious systems worldwide.

Renowned sociologist of religion, Robert Bellay researched and wrote extensively on how religious sentiment evolved over the millennia. Here I’ll focus on what he says concerning a world value assessment within religion. Bellah talks about phases in religious evolution:

“There are 5 major phases in the world-wide evolution of religion. Acceptance of “this world” is emphasized in the first and last phases. Rejection of “this world” is highest in the middle phase, Historic Religion. Rejection of “this world” is a function primarily of religious dualism. Dualism reaches its peak during the historic phase when the “great, universal, ethical religions” emerged—Christianity, post-tribal Judaism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Islam.”

The phase of historic religion is particularly important because it is out of this phase the major world religions came into being and remain dominant worldwide.

Implications

When a particular world assessment is chosen, that has far-reaching consequences for the theology or religious philosophy. Questions beg for solutions. If the question is “why is the world so screwed up?” and the answer comes out of a world-rejection worldview then the answers will almost be inevitable. With a fundamentally flawed world, the obvious answers could be twofold — get out or get something new and better. This leads to two terms used in theology but also apply to religious philosophy — soteriology and eschatology. Soteriology is about salvation schemes. If the world (or us) is so fundamentally flawed, it needs to be saved. So, we get salvation schemes. Those vary among the major traditions and even within them. In mainstream Christianity, the world is flawed because of human sin. This leads to a judicial type of soteriology. The scales of justice must be balanced. They are balanced with the atoning death and resurrection of the Son of God (Jesus). That balances the scales but what about this flawed world. Enter eschatology. Eschatology is about the end times when this eon comes to an end and a new one begins. Presumably, this new eon won’t be flawed like this one. What this new eon is like varies. There could be a new heaven and earth or just some heavenly (unflawed) existence.

Obviously, this mainstream approach has major theological problems. Did God screw up in creating this world? Isn’t the artisan responsible for the artifact? This presents a picture of God as an incompetent creator where a fix has to be applied. So, does God do a better job creating the new heaven and Earth? There are many other problems with this world-rejecting sentiment but that’s not what this post is about.

In the East, this world-rejection also shows up in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Daoism, and Confucianism. What we get also has various salvation schemes and eschatologies. These vary greatly among these religious philosophies but a common thread in Buddhism and Hinduism is “the liberation from or ending of samsara, the repeating cycle of birth, life, and death.” The eschatology may be more of a personal escape or transformation.

The Issue

Theologies and religious philosophies are built on fundamental tenets. They are fundamental for a reason. Fundaments are needed as a basis upon which further explications can ensue. They shape and restrict the system according to the questions asked and answers given. Since they are fundamental, any attempt to change the sentiment is highly problematic. But what if a fundamental worldview is no longer compelling? Again Robert Bellah. The first phase he calls “Primitive Religions” and the last phase (our current one), “Modern Religion”.

“Acceptance of “this world” is emphasized in the first and last phases.”

Studies show that the fastest-growing group regarding religion is the “nones” — no religious affiliation. There are many reasons for this decline but according to studies one of the major ones is that the tenets of a religion are no longer compelling or believable. In other words, they don’t seem to fit in with the current worldview.

Now, broadly speaking, I don’t view this disaffiliation as problematic. I myself became unaffiliated some 25 years ago. However, disaffiliation can have its personal downside. It can lead to a sense of loss and being spiritually adrift. That was my case for a while. Still, disaffiliation can be a motivating force for reassessment. It can lead to spiritual or religious growth.

Now, theologians have recognized this issue for a long time. They, themselves may have experienced a sea-change in their own thinking. So, they responded. I don’t know much about other religious traditions but within liberal Christianity, there have been many attempts to reframe Christian theology to address the changing worldviews. Whether or not some may be effective is an open question. If those changes enhance people’s lives and aren’t harmful, in my view, all the better.

I believe this questioning of ancient sentiment is a positive. Life is about growth and change. A world-rejecting worldview can have significant downsides. It can lead to a complacency toward the serious problems the world faces. If soteriology and eschatology are in the offing, why bother with concerns about the future? If escape or a new creation are the goals, that is a cop-out instead of a sober affirmation of life as it is.

If there is an affirmation of the world just as it is, that changes things dramatically. There is a call to action. I believe one of the goals for this Divine Life is the eternal creation of love, courage, beauty, and meaning. There is no perfection to be attained, only the constant effort to create the good and beautiful. Doesn’t that offer a profound meaningfulness for life? Isn’t that enough?

On this website, I’ve advocated for a divine idealism ontology (also an aspect monism). I’ve talked about this ontology throughout the website but here, in this short post, I’ll discuss one reason why I think it is a crucial step in choosing an ontology that addresses the perennial issues in religious metaphysics.

Human beings have an intuitive sense that there is a profound meaning to the universe, there is free-will, and there are objective values (morality). Why should we accept these intuitions? Basically, because in the ontology employed here, everything has a divine depth that informs us. Here are a couple of short posts addressing this, here and here.

So, how can it be that those issues (meaning, free-will, objective values) are real? Essentially, it comes down to how reality is constituted. The prevalent view among science-minded individuals and even most religious thinkers is that reality is constituted via laws and chance (quantum indeterminism). Accordingly, every event in the universe is determined by necessity and chance. This is a disastrous choice. It means that reality is autonomic, just doing what it does without intent. Since humans are part of the universe and because of the causal chain of events, humans are just automatons. Autonomic systems don’t have meaning, free-will, or values because they just do what they inevitably do.

If we are to affirm the intuition that we are not mere automatons, what ontology can be chosen? I think a divine idealism offers a solution (the only viable one as I see it). In a divine idealism every event in the universe is intentional in the mind of God. This includes the regularities we see (and science tries to characterize) as well as the novelty that indeterminism affords. There are no laws or chance. Everything occurs according to divine purpose. What purpose? That’s a complicated question that I’ve address in many essays but essential it is that the universe is constituted such that, among many other things, those features I’ve mentioned (meaning, free-will, objective value) are possible. The other element of the ontology I employ is an aspect monism. That means that everything (God-as-living) is an aspect of God-as-transcendent and participates in the divine ultimate meaning, freedom, and value. We are not automatons. Instead, we are parts of the Divine Life where we participate in profound meaning, have some freedom, and must make moral choices. A divine idealism and aspect monism ontology offers a way to think about metaphysics where our deep-seated intuitions can be affirmed.

Where It’s Useful

I’m a big fan of simplicity in principle but with one major caveat. Except for a two-year break to study theology, I worked about 40 years as a design engineer designing machines, systems, and software. In that work, simplicity was an important goal. Simpler designs are less costly, easier to manufacture, maintain, and generally more reliable. The fewer “moving parts” in a machine, system, or software the less likely there will be problems with it. But here’s the major caveat. The design had to work. It had to meet the specifications even if that required more complexity.

This goal of simplicity could be broadly understood under the concept of parsimony. One of the most generally recognizable ways of characterizing parsimony is Occam’s Razor, named after English Franciscan friar William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347). Often the Razor is summarized in sentences like: “Entities should not be multiplied without necessity”, or the one most likely attributable to Ockham himself, “Plurality must never be posited without necessity”. The one I particularly like is probably a paraphrase of what Einstein actually said. It goes: “Everything should be made as simple as possible — but not simpler.” The key point in these is that necessity should guide how simple or complex a theory or system should be. So what determines the necessity?

Let me offer an example from my work. When I worked in the aerospace industry, specifications for a system often had hundreds of requirements. Now, here’s a key point. All those specifications had to be met. The necessity was meeting the entire specification. However, one of the prominent specifications, either explicit or implied was parsimony. Systems had to work but if they were unnecessarily complex that could make them very costly to make, maintain, and be less reliable. So, “Entities should not be multiplied without necessity”. Parsimony then is an essential component of the mindset and method of design so that things work well.

Now, let me turn to the use of parsimony in theology and metaphysics. I think the aforementioned understanding of parsimony is also an essential part of the mindset and method of doing them. Metaphysics and theology both require speculations. That is the nature of metaphysics. So, the KISS method (“keep it simple, stupid”) should be taken seriously. However, there is also a constant dialog going on. Every step in a design (theological or metaphysical) constrains what can come next. So as the design process unfolds, every step along the way must try to anticipate the consequences for what will come later. If this is not taken into account, entities will have to be multiplied later to compensate for this lack of foresight. When that happens things can get out of hand quickly and create more opportunities for the system to become incomplete, incoherent, contrived, or inconsistent. So, the challenge for these types of systems is finding one that works (more on this in a bit) without creating complexity beyond necessity. To do that one needs to think about the entire specification throughout the design process.

Where it is Misused

Parsimony is misused in metaphysics when it is used as an argument. There are several ways the concept of parsimony can become problematic. Metaphysicians and theologians try to make arguments for why their formulations are right. Fair enough. They offer exhibits like data, logic, consistency, coherence, explanatory power, and so on. However, if parsimony is used as an exhibit — an argument, that is problematic. It’s problematic because it can lead to a misunderstanding, be counterproductive, and/or be misleading.

The first way it can be misunderstood is when it is really an argument from simplicity. There is a major difference between “not multiplying entities beyond necessity” and an argument from simplicity. Parsimony is neutral on whether or not an explanation will end up being simple or complex. It simply suggests that it is best to not go overboard with speculations when they are not necessary. However, if the argument-from-parsimony is really an argument from simplicity that has a presupposition embedded in it that fundamental reality is simple so it can or should be characterized in a simple way.

An example of this type of inclination can be found in physics where there can be a presupposition of simplicity such that major efforts and resources are committed to finding an equation that completely explains physical reality but can also fit on a tee shirt. Now, I don’t think searching for such an equation is problematic itself, but if there is a driving desire for such a simple solution, that can be counterproductive and prematurely cut off entertaining other more complex options. This could also apply to metaphysics.

However, the most abused form of parsimony-as-an-argument comes in from the very nature of metaphysics. Almost invariably metaphysics is systematic. Systematic metaphysics is a complex arena. There are many parts to it that are relational and often combinatorially so.

What characterizes a system? It should be coherent, logically sound, consistent, complete, rigorous, and elegant(including parsimony in the first sense I mentioned). There is so much going on in these systems that parsimony-as-an-argument, if used, would have to apply to the whole system. Since there are so many interrelational parts involved, how could parsimony possibly be asserted coherently? At best it would be just a vague intuition and not definitive at all.

So, for those who are trying to evaluate a metaphysical system, an invocation of parsimony could be misleading. An argument is supposed to contribute to the validity of an explanation or solution. But does parsimony really do that in systematic metaphysics?

A way to approach this question is to look at it pragmatically. To use an engineering phrase: “Does it work?” That depends on what “it works” means. To answer that we’d have to look at the domain of “it works”. Does it meet the entire “specified requirements?” One way to think about this domain is to determine what questions are being asked. Metaphysics is an attempt to speculated beyond “the physics” which means explanations are sought that offer answers to certain questions. If parsimony-as-an-argument is invoked, almost invariably the domain is very restricted. This can be misleading because as the system expands beyond that limited domain and tries to offer answers to the full gamut of questions, the so-called parsimony can evaporate with a series of ad hoc assertions, questionable brute facts, or odd contrivances in an attempt to make things work. This is why seeking parsimony-as-an-argument for a system is ill-conceived and often misleading.

Let me offer a couple of examples where I think this issue can be the case. The problem of subjective experience or phenomenal consciousness has found a lot of interest among philosophers of mind and in social media. How do we explain subjective experience within present worldviews? Materialism (a.k.a. physicalism) seems to have a problem with this. I won’t go into this question in depth here but among the proposals getting traction that supposedly offer better answers than materialism are forms of panpsychism and idealism. There are many varieties of these but in some of the prominent ones, the idea is to make experience fundamental. If subjective experience doesn’t fit in with materialism, why not just make it fundamental? So, in these systems, experience is what might be called the ontological primitive upon which everything else is built. Some forms of idealism have called this the “consciousness only” model. (Note: This is very different from the divine idealism I argue for on this website.)

So, what are the arguments for this approach? Prominent among them is an argument-from-parsimony. Supposedly it’s the simplest explanation that accounts for subjective experience. Now, if the question of subjective experience is the complete domain of interest, parsimony-as-an-argument could carry some weight. But is that really the total domain of questions? Hardly. First, when a simple primitive is posited as fundamental then how are the complexities we see accounted for? For example, in physics, the standard model has various types of particles (or excitations in quantum fields) and the four fundamental forces. So, this physics model is complicated. To be consilient with this model, the experiential fundamental would have to be more than just a raw experience. There would have to be some relational dynamics also in play that mirrored things like mass, spin, charge, as well as the strong and weak nuclear forces, gravity, and electromagnetism or the fields associated with them. Suddenly, experience as a fundamental becomes much more complex with lots more going on than just a raw experience.

Then for human beings, there is much more. In systematic metaphysics, all related issues need to be addressed. They can’t be ignored because inevitably these other issues will enter into the conversation. We see this in interviews, podcasts, and videos. Questions are posed like “what does this say about the meaning of life?” or “does free-will fit in somehow?” or “what does this mean for morality?” Eventually, existential issues like meaning, free-will, purpose (teleology), morality, and so on, are raised because metaphysics isn’t taken as just some neutral puzzle-solving endeavor.

How would a so-called simple fundamental answer those questions? Is there a meaning principle in experience? Is there a free will process in experience? An experiential purpose element? A value law? And so on. Again, suddenly a so-called parsimony begins to seem suspect. To make it work what we might see are odd contrivances, equivocation, obfuscation, and ad hoc postulates or brute facts. In other words, “entities will have to be multiplied” to make the system work.

Now, perhaps there are ways to make this “consciousness only” model work. Time will tell. My point is that parsimony-as-argument based on an extremely limited domain is ill-conceived for systems. For systematic metaphysics, parsimony-as-an-approach is a perfectly legitimate aim but as-an-argument it shouldn’t be given any weight.

Why this might matter?

Human beings are meaning-seeking creatures. Without a sense of meaning all sorts of psychological problems arise. To a large extent that meaning comes from a worldview — who and what we are and our place and relationship to reality. In every age, there are many worldviews in operation. They vary not only among individuals but also between cultures. Often they form a basis for how lives and societies are structured and operate.

It appears we are in one of those periods in history where there is a growing trend to reject past worldviews and the metaphysical systems that support them. They just aren’t compelling to many people. Of course, this is nothing new. There have been periods of relative stability where certain worldviews were generally accepted for long periods of time. However, as things change in culture and knowledge that can present challenges to a current metaphysical system or religious tradition.

As an example, polls have shown that the fastest growing group relating to religion are the “nones” — the unaffiliated. This is particularly true for younger people. Whether or not this is problematic for someone depends on the individual. I can speak from personal experience because I became unaffiliated over 30 years ago. There can be a sense of loss but it can also be liberating. However, for me, it also created a feeling of being adrift religiously. I remained a theist but wasn’t sure what that meant for me. That situation was the impetus for me to work on the theology found on this website.

So, there is a growing number of those who do not feel the religious traditions compelling anymore but there may also be others who are outside the traditions and have an uncomfortable feeling about the worldview they presently feel aligned to. These could be atheists, agnostics, or those who do not have a religious background. If there is this metaphysical unrest then what is a person to do? Often this results in a search for something to address that unrest. It may start with surveying long-standing metaphysical systems. If those don’t seem right then it may broaden to new approaches. As far as I’ve been able to ascertain, there haven’t been many new systematic metaphysical systems recently. I can think of a couple — process philosophy and integral theory (Ken Wilber), but there does seem to be more on the horizon coming from the philosophy of mind arena like those I mentioned earlier.

The question is, how can they be assessed and which ones seem compelling? What criteria or reasons can be brought to bear? Well, obviously this can vary greatly from person to person. For some, it may be primarily intuitional but for others, a more explicit, detailed, and rigorous approach is needed. If the latter is the case then arguments are important.

Now, since the religious traditions have become a disappointment to many, the last thing those searching for their metaphysical bearings would want is to entertain a new metaphysical system only to find out later that it had deep flaws concerning the most pressing existential issues I’ve mentioned. This is why I think it is important to be clear about what is being argued for in a metaphysical system.

Accordingly, I think too much illegitimate weight is put on parsimony-as-an-argument for metaphysical systems. Claiming parsimony as a major argument for a particular system can be so misleading I don’t think it should be used at all. Systems are far too complex, combinatorial, and interrelated to claim parsimony. Instead, the totality of arguments within a system that addresses all relevant issues should determine whether the formulation is compelling or not.

I recently watched yet another video on free-will. Boring. Same old, same old. So here’s the deal. How is reality constituted? If reality is constituted by laws and chance then any attempts to rescue existential concerns like free-will, meaning, moral objectivity, and purpose are hopeless. Why? Because that means everything at all levels of complexity are determined by necessity (laws) and chance (quantum indeterminacy). The causal chain, no matter how complex just does what it does and can’t do otherwise. If this is the case then everything, including the human being, is just an autonomic system. That should be a straightforward conclusion, right? Apparently not because so much effort is put into somehow spinning this obvious conclusion with all sorts of linguistic gymnastics, obfuscation, or some sort of magic. I think enough is enough. With all the attempts over the centuries to overcome this conclusion it should just be accepted as futile.

So, if this situation is untenable both existentially and psychologically then what might be the options? One option maintains the law-and-chance model but seeks to overcome it with supernaturalism. In this approach, laws and chance are affirmed but the way to avoid the fatalism entailed is to override those laws and chance at times. Now, since we are talking about free-will this overriding isn’t just occasional. It’s happening all the time. Every free decision must override the necessity and chance inherent in how reality is normally constituted. Also, in the ontological dualism of standard theism, this means every free creature is also a supernatural agent.

If the supernatural model seems odd or not appealing what might be another option? Enter divine idealism. In divine idealism reality is constituted by the divine mind. So, every event is intentional and includes divine freedom. There are no laws or chance. Everything, down to the most elemental event is intentional. Now, that doesn’t mean there are no regularities. That would entail a chaotic system that wouldn’t make life possible. We empirically affirm and characterize those regularities with scientific investigations. Also, from science, reality seems to be constituted with a statistically consistent framework. Not just anything goes. In a divine idealism, there are divine self-imposed constrains in how the divine mind constitutes reality. Here you can think of how you would imagine and construct a story in your own mind. It would have regularities that made the story possible and coherent but it would also not be autonomic with no novelty or freedom. Everything would be intentional with a constrained freedom that still maintained a stability.

I think this is a valid, reasonable model for how reality is constituted that would allow for free-will, meaning, objective morality, and purpose. If reality is constituted by the divine mind and each life is an aspect of that divine mind then the freedom, meaning, and value of the divine mind is shared with finite creatures within some constraints. We aren’t supernatural creatures but rather participants and co-creators with God-as-transcendent in how reality is constituted both for ourselves and the cosmos.

There are metaphysical systems that claim reality is constituted non-intentionally. In this worldview, there are non-intentional laws and processes that create reality at every level. If that constitution is non-intentional then existential concepts like purpose, objective value, free will, and meaning are vacuous because no matter at what level of complexity there is, it’s just autonomic processes doing what they inevitably do with no free choice. For thinking and sentient beings, this presents an absurdity. Why? Because those beings have a profound intuition that those existential concepts are not just an illusion perpetrated on them by non-intentional processes but are real. Also wouldn’t it seem absurd that all this — the entire universe and all the beings in it are just meaningless autonomic processes just doing what they do.

This absurd sense becomes apparent when we see the extraordinary lengths those who profess that worldview go through to salvage them somehow. These attempts always fail with a necessity and chance causal structure that a non-intentional constitution entails.

Now, an argument from absurdity is considered a logical fallacy. So what? This only carries weight for those who think that logic alone can capture the essence of reality. Sure, without logical constructs there can be a descent into nonsense. What is often missed, however, is that logic is grounded in our intuitions about how things work. If logic alone was determinative then we would expect that analytic philosophy would have eventually reached a consensus of conclusions. Not even close. Something must be missing. Can the structure we see be just part of the picture? Perhaps the structural aspect provides the stability that life can exist but there is also novelty within constraints that offers the meaning and purpose we intuitively feel.

There is a reason humans personify the ultimate. If the ultimate is personal then it is intentional as well — and relational. Even non-theistic religions like Buddhism have personifications among adherents. We want to be in relation with the universe and beyond. Without a relationship to the ultimate we are alone and isolated. As finite creatures this doesn’t work. It deprives us of a sense of being part of something profound. If taken seriously, that only leads to despair and nihilism.

So, there is a choice. We can obscure the absurdity of being an automaton through ignorance, denial, or repression and just carry on. Or we can embrace that there is a personal, intention ground to reality that we can relate to and be a part of something profound going on in this life.

There are a lot of terms bandied about regarding the metaphysical foundations of reality. Some are physicalism, materialism, panpsychism, idealism, theism, deism, pantheism, panentheism, etc. Of course, the devil is in the details of what these really mean. Here I’d like to distill this down to a couple of terms that I think indicate an essence of these terms. Those terms are intentionality and non-intentionality. At the bottom line, the question is, is there intention or non-intention fundamental to how reality gets constituted?

Intentionality has certain features. First, there is a goal or purpose in mind. Intention isn’t just happenstance. It is about something. If there is a goal then there must also be some value system at work. If there is a goal in mind and values at work then that means there must be options. Without live options, intentionality is meaningless. If there are live options, that means that there must be freedom to choose from them. Choices and actions must be evaluated according to their effects, and decisions must be made based on all that. We all know this intuitively from our own sense of self. Without intentionality, the only thing left is fatalism — things just happen for no intentional reason. Non-intentionality has none of the features of intentionality. Stuff just happens.

So, what has all this to do with fundamental reality? A lot. That’s because of causation. We know things happen within a causal chain. One thing causes another. The chain may be short, say in a rock falling to the ground or it may be highly complex like in the neural networks of the brain. But causes beget effects which, in turn, beget other causes. If fundamental reality is non-intentional then every step in the causal chain is also non-intentional. Unless magic is invoked, there is no place for intentionality to come in. So, no freedom. No value. No meaning.

Now, if someone acknowledges the fatalism in the non-intentional approach, fine. At least they are being honest. This rarely happens. Why? Because it’s hard to swallow that worldview. So, what happens? A lot depends on influencers. These are public intellectuals who know the details of arguments and promote their worldview to others. Now, since the fatalistic worldview is abhorrent to many in the public, what are they to do? In short, equivocate. Definition of equivocation: “the use of ambiguous language to conceal the truth”. The general public might not know the nuances of the argument so they are ripe for being misled. All that is required is to throw in a few equivocated intentional terms in the non-intentional presentation and the public will be none the wiser. Examples are free-will in compatibilism or teleology when teleonomy (no real purpose) is what is meant. Terms like meaning and purpose are often used when they are vacuous in an autonomic universe.

A reality grounded in fundamental intentionality can offer so many things we existentially feel we have and would like. Meaning, purpose, free will, moral objectivity, etc. are all in the offing. So, when evaluating a particular metaphysical system perhaps it can be helpful to ascertain if what is being promoted is fundamentally intentional or non-intentional.

Most people don’t like to think of themselves as automatons — just inevitably doing what they do. But that is the logical inference if reality is constituted by necessity (laws) and chance (quantum indeterminacy). So what do those who subscribe to the non-intentional model of reality do? There are numerous attempts to somehow salvage free will. Some are just nonsense like compatibilism and others try to find some way to use indeterminism. None of that works if necessity and chance determine every event in the universe.

Another thing most people want to believe is that we make conscious decisions. Here the key word is “conscious”. But how would that work? After all, we know that most of the decision-making process is done unconsciously. There are billions of neural processes going on that we have no awareness or experience of. It’s only very late in the process that we experience a decision. So, there is all this processing going on unconsciously and then after all that is done there is suppose to be some other different conscious processing that makes a decision or vetoes the decision make unconsciously. In that case there seems to be a phenomenal (experience based) homunculus (some extra something that has its own decision making processes). Seems like a weird contrivance to me.

Now, even if any of that were truth the missing necessary element in those schemes would be why a certain decision is made. The unconscious neural processes have all sorts of biases in their circuits that determine the processing at every step. Here you can think about a single neural synapse that has a chemical/electrical bias to react a certain way because of an input. Now, obviously there is an incredible complexity at work with all parts of the brain interacting but in the non-intentional model the brain just does what it does, much like a computer. In a computer each bit sets its state based on the input to it. It has a bias that responds to an input.

So in the non-intentional model, our unconscious processes do their biased thing and eventually end up with a decision (sometimes through a very tortuous process). Then the homunculus steps in and accepts or rejects that? Based on what? This is the missing necessary element in this scheme. There should be some other criterion for making a different conscious (homunculus) decision than what the neural process came up with. But what would that be? The non-intentional constitutionalists would need to come up with something here. In years of following this topic I haven’t seen anything like that.

So, instead of the non-intentional approach, here’s what I think may be going on. In a divine idealism every event in the universe is intentional. There are no laws and no chance. Everything happens because of intentionality — both the regularities and novelties. This includes everything in our brains. Every event happens for a reason. Those reasons are twofold. They are twofold because they include those of God-as-transcendent and God-as-living. I’ve talked about this elsewhere — and will in more detail on how this might work in an upcoming essay on divine action. So, the issue at hand is what is involved in why we make a certain decision?

Now, here I’m going to speculate from physics but based on some mainstream models. I think that every event in the universe is connected and integrated with everything else. Thus decisions are not just something “magical” happening. They occur within the life giving constraints of this reality.

In the divine idealism model, there is a teleological impetus involved in every event, even at the microscopic level. I’m using the term “impetus” because it denotes an active, forceful factor. As an analogy, think of how a magnet applies a force to attract a metal object. This is not some passive “lure” like in process theology. It is an active (but not coercive) influence toward a certain direction. The force of the magnet can be resisted but it is still an important factor in a decision. God-as-transcendent provides an impetus according to the divine purposes for this reality. However, God-as-living (that’s us and everything else) also has internal impetuses at work. These ensue from being finite creatures with certain motivations, needs, and desires. Sometimes there may be a competing impetus. I think that competition can occur at every step in the decision making neural processes, not just at the end. Every step is part of an integrated whole within the Divine Life Communion. What this means is that at every point in the process a decision must fit within the statistical model of how reality is constituted and take into account what is possible within those bounds. However, novelties can also occur within those bounds. So, live options are available. At various points in the process the competing teleological impetuses can become pronounced and a decision must be made. There is a constrained free will at work here. Each decision narrows what is possible. Eventually a final decision is made. It’s a decision on what impetus we freely choose to win out.

So, where does consciousness come in? I’m not sure about this, but to avoid the homunculus scenario, I think what consciousness does is experience the decision we made unconsciously. Now some might say, well “that’s not me making the decision”. Of course it is. That would be like having a back pain and saying, “that’s not me I’m experiencing”. A person is a whole, including their unconsciousness. If that wasn’t the case then the “me” would be different from everything else going on in our bodies.

So, the necessary element in free will is the reason for making a decision. That reason comes down to making a free choice between the sometimes competing impetuses of God-as-transcendent and God-as-living. God-as-transcendent has a purpose in mind for this reality. I think a big part of that purpose is the creation of love, beauty, and meaning. God-as-living, as finite constrained beings also have impetuses. The question is which impetus to embrace and act on.