Today I’m going to psychologize a bit concerning the formulation and evaluation of worldviews and metaphysical systems. In 1994, I read the book “Descartes’ Error” by neurologist António Damásio. It was a game-changer for me. At the time, I subscribed to a common notion that emotions could be the bane of being rational. Both Plato and Aristotle felt that reason was superior to emotions or as they called them, the passions. The idea is that emotions can taint reason. This view is understandable because who hasn’t seen either in themselves or others where emotions can lead to unreasonable conclusions? I felt the same way. However, that view changed after I read Damasio’s book. There were similar books like Joseph Ledoux’s “The Emotional Brain”.

What Damasio and others showed was that emotions aren’t just some independent force tainting reason but actually an intrinsic and necessary part of reason. In his book, he talks about several real-life examples of what is going on. These examples illustrate what happens when the parts of the brain associated with emotions become damaged. A famous example of this Phineas Gage. Gage was a construction foreman who was installing an explosive charge into a hole in a rock. An accidental spark ignited the charge and drove a tamping iron through his left eye and into his left frontal lobe. He survived that accident, but his personality was changed forever. Contrary to his previous personality, he became volatile and profane with poor judgment and the inability to take on complex tasks.

An even more striking example Damasio recounts is a man who by all accounts was a perfectly reasonable, rational individual, well known for his judgment in complex issues. This man, however, sustained a lesion in an area of the brain known to be responsible for emotions. While not life-threatening, this damage had a lasting effect on the man. His psychological affect (emotions) became subdued. Also, whereas before his judgment was unassailable, after the disease that changed dramatically. He was able to reason just as well as before but unable to make good judgment calls. He had great difficulty in making decisions and as a result, his judgments were suspect. Something was missing. That missing component seems to be emotion.

What are we to make of these examples? What Damasio and others claim is that emotions are a critical element in making judgments. They are not necessarily a taint on making well-reasoned judgments but instead are crucial for them.

So, what’s going on with the process of reason? There is obviously a strong element of logic involved. The structure of logic creates guard rails within which the process can proceed, avoiding wild unsustainable threads of thought. However, logic is not some sterile, simple process. Logic requires language and language is inherently value-laden. Each step in reasoning has a value associated with it. In a simple case, this valuation is embedded in subscribing to things like the law of noncontradiction or the excluded middle. It can also be encoded in a list of logical fallacies. These are all value-laden because there is a sense of wrongness (a value) to them. In other words, emotions are in large part about valuations. The reason emotions manifest themselves in physiological ways (feeling good, being anxious, rapid heartbeat, sweating, feeling calm) is because there are deep-seated values at work.

This value may not be something simple but rather a combination of many factors. However, even with its complexity, in the gestalt (holism), it offers a weighting force. It pushes the reasoning in certain directions.

Emotional Commitments

As life proceeds from childhood, various emotions are imbued within us. These proceed from both positive and negative experiences. Early on, pleasure and pain play a pivotal role in the valuations we make about circumstances and our response to them. As we get older, our valuations become more complex and nuanced. Still, these emotional (valuational) responses shape how we will evaluate what is presented to us and influence our response. There are what I’ll call “emotional commitments”. A commitment is a strong bias toward something. However, all commitments have an emotional content. That’s because there is always some value associated with it. These commitments are deeply engrained within us and almost autonomic. One might call these “knee-jerk” responses just like those tested in the doctor’s office. This can be advantageous because we can make very fast decisions. It can be valuable in certain circumstances but also problematic if those biases are counterproductive. The point is that we all have emotional commitments toward a certain perspective of reality. Those commitments shape how we will evaluate new experiences and information as it arrives. Depending on what those commitments are it can create either a blockage or openness to the new we experience and what it entails.

Metaphysical Emotional Commitments

Is there any doubt that there are strong emotional commitments in metaphysical worldviews? One has only to witness the heated arguments among opposing worldviews. Metaphysics speaks to “beyond or underlying the physics”. Since the foundations of reality are underdetermined by our knowledge and perspective, metaphysics speculates about the unknown and what it might mean. As such, there are existential concerns (life, death, meaning, freedom, value, etc.) in the balance. These concerns reflect our sense of self and the meaning of our lives. No wonder there are emotions involved.

For millennia there have been many metaphysical formulations offered. They try to offer a picture of reality that addresses not only what empirical investigations suggest but also existential concerns (what we care about deeply). For those interested in creating or evaluating metaphysical systems, I think emotional commitments should be considered. What might those be?

Emotional commitments are as complex as individuals. They stem from the entire history of the individual as well as their engrained makeup, be it genetic or cultural. As psychology has shown, they may even be a mystery to the individual, buried within the unconscious mind. However, if an effort is made, they can become somewhat apparent if probed. If that task is undertaken, perhaps it can inform future choices.

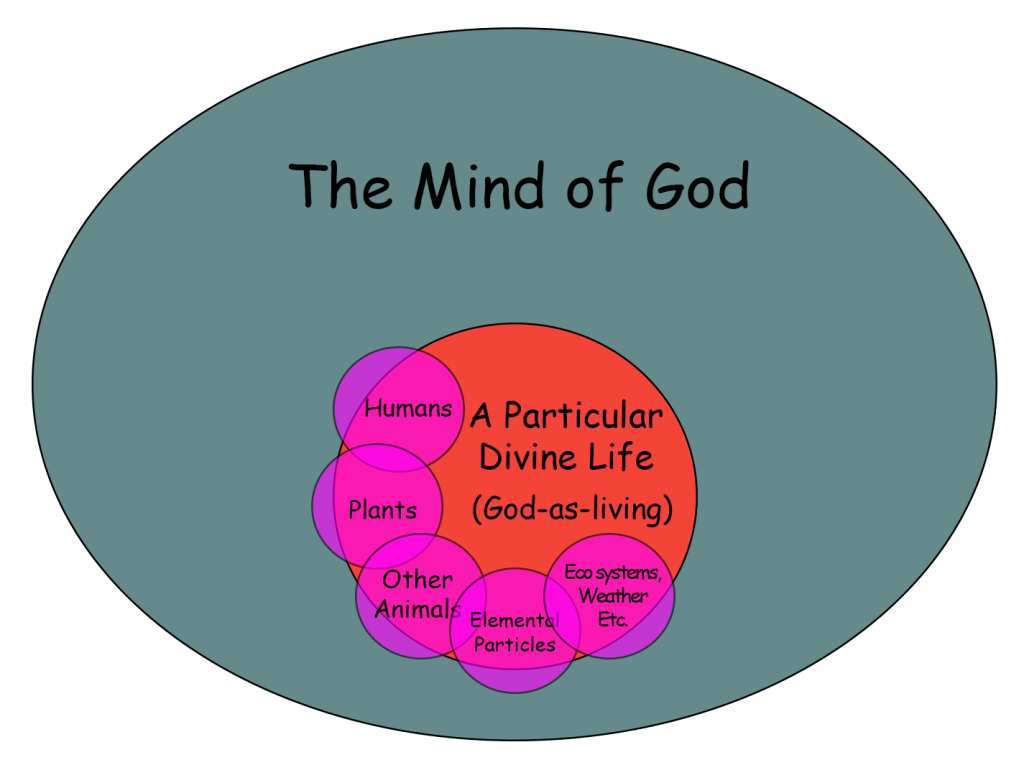

At this point, I think it is also important to understand that there is a hierarchy and interaction of these emotional commitments. Some provide more force than others. There can be competition among them. They each have a certain weight in the evaluative process. This can create what psychologists call a cognitive dissonance. I offer a metaphysical metaphor about this here. As the mental process proceeds, inevitably the strongest emotional commitments will have a strong influence on the result, often tipping the balance.

Also, another factor could be called the domino effect. In this effect, if one particular domino (say a proposition) falls then many subsequent dominos will fall as well. There is an entailment of ideas. This can be rapidly assessed in our minds. If this happens the emotional response can be multiplied enormously. Each domino represents some emotional commitment.

Here, I’ll offer an example within religious thought, but it can apply, as well, to other metaphysical worldviews. Religious philosophers, theologians, and adherents are a varied bunch. They each have their own histories and personality types. They also have their particular emotional commitments. What might those be? There is a continuum for these commitments.

For some, there is a strong emotional commitment to certainty. We see this with evangelical theologians and adherents. It is very important to them to have a sense of certainty regarding the worldview that ensues from the philosophy or theology. For some, this means a commitment to the inerrancy of some scripture or religious text. If that domino were to fall the subsequent falling of other dominos may be more than they could emotionally bear.

At the other end of the continuum, there are religious thinkers and adherents who aren’t that concerned about certainty, and no matter how incoherent ideas may be, they are perfectly willing to accept them.

In between is where we find most of these religious thinkers. There is a commitment to rigor but also an acceptance of some level of uncertainty. They recognize that metaphysics is speculative and underdetermined.

Since we are all existential creatures, this same emotional dynamic applies across the board for any system that impinges on our existential interests. This includes metaphysical systems like atheism, theism, non-theism, agnosticism, materialism, and the like. The question to ask is what are the emotional commitments and their weighting power?

If the strongest emotional commitment is sustaining a particular worldview, that will guide what can follow and be entertained. If the strongest commitment is toward certainty, that will narrow what can even be considered. If, however, the dominant emotional commitment is to the truth, that can trump all other commitments. Obviously, that can be scary because it may mean abandoning or modifying a worldview. Not an easy task.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, creating or evaluating a metaphysical or theological system is a judgment call. However, in that process of creation or evaluation, there can also be a probing and evaluation of the personal emotional commitments that are at work. Are the commitments strongest toward the truth or are they aimed at sustaining a current position? This can be difficult to determine and requires courage to go there but if taken seriously it might result in a more stable and less conflicted state.