This is a response to an article in Scientific American by Bernardo Kastrup, Adam Crabtree, and Edward F. Kelly, idealism proponents, where they claim that an analogy with dissociation (as Kastrup discusses) like that found in the dissociative identity disorder (DID) can offer a solution to “a critical problem in our current understanding of the nature of reality”. That problem being the combination problem in panpsychism where the question is, as David Chalmers briefly puts it — “how do the experiences of fundamental physical entities such as quarks and photons combine to yield the familiar sort of human conscious experience that we know and love.” The authors of the article respond to the problem with an alternative view:

The obvious way around the combination problem is to posit that, although consciousness is indeed fundamental in nature, it isn’t fragmented like matter. The idea is to extend consciousness to the entire fabric of spacetime, as opposed to limiting it to the boundaries of individual subatomic particles. This view—called “cosmopsychism” in modern philosophy, although our preferred formulation of it boils down to what has classically been called “idealism”—is that there is only one, universal, consciousness. The physical universe as a whole is the extrinsic appearance of universal inner life, just as a living brain and body are the extrinsic appearance of a person’s inner life.

However, the authors also recognize a potential problem:

You don’t need to be a philosopher to realize the obvious problem with this idea: people have private, separate fields of experience. We can’t normally read your thoughts and, presumably, neither can you read ours. Moreover, we are not normally aware of what’s going on across the universe and, presumably, neither are you. So, for idealism to be tenable, one must explain—at least in principle—how one universal consciousness gives rise to multiple, private but concurrently conscious centers of cognition, each with a distinct personality and sense of identity.

They think the solution can be found in an analogy with dissociative identity disorder:

And here is where dissociation comes in. We know empirically from DID that consciousness can give rise to many operationally distinct centers of concurrent experience, each with its own personality and sense of identity. Therefore, if something analogous to DID happens at a universal level, the one universal consciousness could, as a result, give rise to many alters with private inner lives like yours and ours. As such, we may all be alters—dissociated personalities—of universal consciousness.

This would seem to satisfy the conceivability requirement in philosophy of mind proposals and suggest some details about what is happening, but at what cost? There is a negative connotation associated with DID. It is considered a disorder, perhaps stemming from pathological inabilities to cope with life as a unified personality. F. C. S. Schiller in his 1906 paper, “Idealism and the Dissociation of Personality” affirms that this analogy does solve some problems for idealism but also recognizes that it carries a negative connotation for the absolute:

Moreover, (2) if the absolute is to include the whole of

a world which contains madness, it is clear that, anyhow, it must, in

a sense, be mad. The appearance, that is, which is judged by us to

be madness must be essential to the absolute’s perfection. All that

the analogy suggested does is to ascribe a somewhat higher degree

of reality to the madness in the absolute

While I appreciate the intent of the dissociative analogy to address a problem, if analogies can offer some credence to idealism, then perhaps there are other real-world analogies that are reasonable but do not carry the negative connotations. So, I’ll offer a couple of analogies here that might also be viable but are positive and affirming for why the diversity in the cosmos came about and do not imply a dysfunction within the Divine Mind. Instead, they imagine a God who embraces taking on constrained being even with all its difficulties and challenges. Given all the problems and evils within life, this must mean there is something so very important and valuable about life itself.

Actor/Role Analogy

It is well known that many actors relish taking on challenging roles. It helps them grow as actors and, perhaps on a personal level, presents unique opportunities to plunge deeper into the human psyche, both theirs and others. So, they research the role, often talk to those whom they will portray, and try to create that role in their mind. Then in the scenes, they shift gears from their normal selves to that role even if that role is diametrically opposite to their normal self. They compartmentalize the role within themselves and act within that compartment, but they still have a unitary self, unlike dissociated personalities. Then when the scene is over, they shift back to their normal selves but they may also experience some change because of the experience of “the other self” in the role. This could represent God-as-transcendent, being changed by God-as-living in each aspect of the Divine Life. What this analogy suggests is that God seeks out the challenge of living perhaps because it evokes the most admirable qualities — courage, resolve, grace in the face of adversity, altruistic love, concern for both self and others, progressive action, growth, etc. In other words, God taking on somewhat distinct lives is not out of dysfunction but rather because God saw something so wonderful and valuable about living within constraints.

MMORPGs Analogy

MMORPGs is an acronym for — Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games. These are online games where multiple players take on certain character types and play those roles as the game dynamically emerges. Those roles can vary dramatically just as personalities can. There can be noble, evil, good, childlike, magical, non-human, conflicted, etc. roles, each with its own personality, characteristics, powers, frailties, and histories. There is also the environment within which the RPG is played. It could be realistic or fanciful. In essence, it is an imagined world with imagined characters that navigate the dynamics of a certain broad narrative. Each player adopts a role and suspends their own self as much a possible to play that role, often within a team of other role-players. It is a simulation of life with all the intricacies of psychology, sociology, culture, and challenge. Why do people seek out and participate in these games? Similar to the Actor/Role analogy, because it offers opportunities to embrace the multidimensions of life in an alternate reality that is both fun, interesting, and satisfies our need to be challenged, grow, be social, and reach out beyond the limitations of our ordinary life.

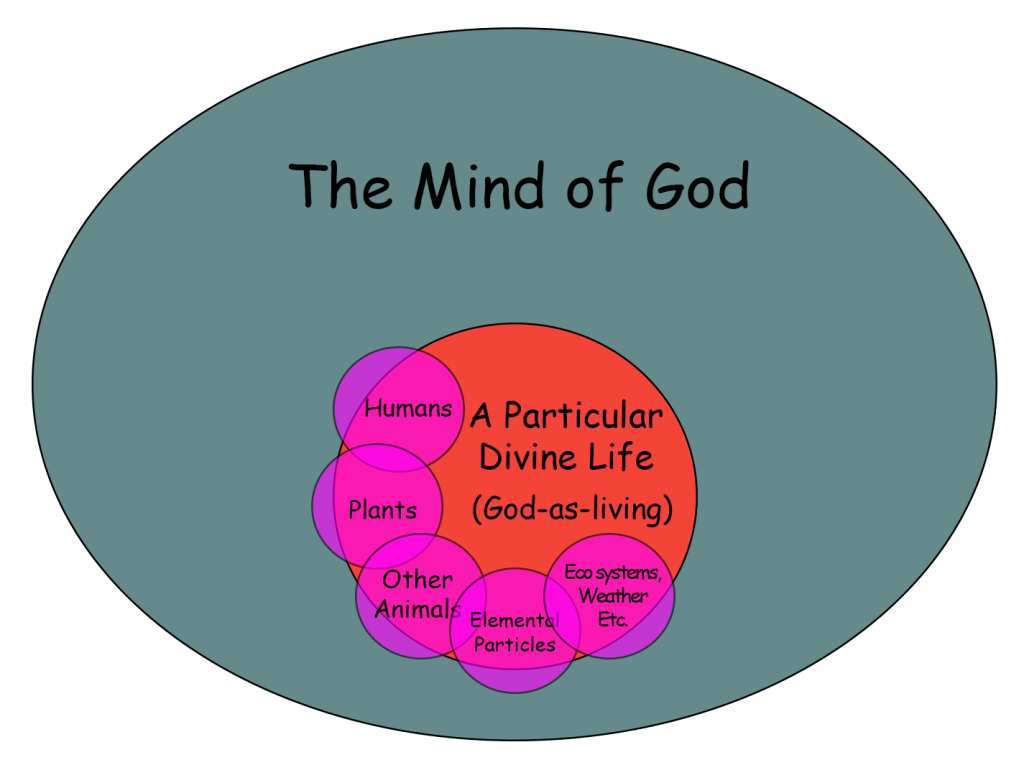

So, what’s the analogy? The analogy is that whereas in online role-playing games there are many separate people playing the roles, in the Divine Life, God is playing all the roles including the role of the environment. Each of us and everything else is an aspect of the Divine Life, created (imagined) in the Mind of God. We are in God’s unitary mind but also distinct and somewhat independent, living our lives within the grand divine narrative where we also must make choices whether or not to embrace the transcendent divine depth within and actualize the divine vision for how life can be.

Now, the limitations of using analogies toward metaphysics should be recognized. They come from within our limited, constrained being and, as such, shouldn’t be taken too literally. Perhaps they can be accepted as metaphors — while of limited literal value perhaps they also point to some deep truths.

Here are some other posts on analogies/metaphors:

Author/Story

Actor/Role

Role Play Games

Venn Diagrams

Divine Action and a Juggler