Metaphysical systems including theology and religious philosophy try to characterize reality in its totality. However, as finite creatures, we have certain abilities and limitations for attaining and expressing knowledge. Those limitations and abilities include perception, cognition, intuition, and language. We can avail ourselves to empirical investigations (science) as a resource for characterizing reality but that also has limitations for how deeply and comprehensively we can probe reality. So, when faced with those limitations, if the goal is to characterize reality in total then a certain amount of speculation is necessary. We even see this in science with the many different interpretations of quantum mechanics.

So, the question is how to approach the characterization of reality in theology and religious philosophy? Since speculation is necessary, the method chosen for this endeavor will affect whether or not the system will be complete, coherent, comprehensive, and compelling. If we look back in history at these systems, I think a useful way to think about the method employed is in the form of question/answer. This is particularly true for those systems that focus on existential issues (what we care deeply about). In that case, the questions addressed are not just out of idle curiosity. They are momentous for how we perceive ourselves and our place in the cosmos and beyond.

Now, every era may have somewhat different questions. This is because our understanding of “how reality is and works” changes as new information and ideas come in. While our perceived understanding of “the more” (as William James puts it) may shift somewhat, certain questions persist and need to be addressed anew.

Questions

The thing about questions is that they shape what answers can follow. If certain questions are emphasized, then the answers will be focused on accordingly. For instance, if the question is “why is there evil in the world?”, the answers will be formulated for that question and may or may not address other existential questions. If the question is “how is reality constituted” (comes about the way it does)?” then those answers may be somewhat different. Or, “what is the meaning of life?” or “what happens when I die?”. Now, it is important to realize that questions can also be nested within one another. They may be in a dialogical relationship with each other where no sharp boundaries can be made.

So, a key issue for why a certain metaphysical system takes its form is to ascertain what questions are being asked. Is the focus narrow or are all metaphysical questions addressed? This is a crucial issue for systematic metaphysics because if the scope of answering doesn’t address all the existential concerns, two things can happen. First, it can become irrelevant for those seeking more complete answers. And second, when confronted with the challenge of a broader scope of questions, the answers can become contorted with ill-conceived contrivances, questionable brute facts, equivocations, semantic games, and the like. The net result is that the system becomes impotent or at least not compelling as an answering metaphysics.

For a theology or religious philosophy, what might those pressing questions be? This is where personal diversity comes in. Questions typically arise out of a puzzlement or discontent in life. For a certain group of people, the questions might be:

- Why did such and such happen?

- Why is life so hard?

- How can I change for the better?

- What should I do in this situation?

- Why do bad things happen to good people?

- What is the meaning of my life?

- Many other everyday questions.

For those who might be more philosophically minded, these everyday questions translate into foundational questions:

- Is there ultimate meaning?

- Is there a purpose to life and an individual life?

- Are there values that aren’t just subjective preferences (moral realism)?

- Is there free-will (could have done otherwise)?

- Why is there evil?

- Is ultimate reality personal (relational)?

- How should I live?

- What happens when I die?

- How should I think about the world (as it is)?

Answers

Answers to these more philosophical questions tend to get complex because there are many interrelated components within these systems. Questions beget other questions and then other questions. However, there are certain fundamental questions that when answered a certain way form a worldview that has an existential impact. I think the scope of questions can be distilled down a bit more to a few that form a foundation. The answers to these questions then lead to fundamental assertions for the theology or religious philosophy. Here are the ones I would choose as fundamental questions:

- Is there ultimate meaning to life?

- Is there an ultimate purpose playing out in life?

- Is there free will (could have done otherwise)?

- Are there values that are not just subjective preferences?

- Can I relate to an ultimate reality?

Individuals have certain intuitions about these deep questions. Most people see themselves as agents who can and must make certain decisions with free will. They also feel there are intrinsic(objective) values that are not just subjective preferences. They intuit there is an ultimate purpose and meaning to life. They feel or want a personal relationship with ultimate reality. They sense that they and everyone else are part of some grand narrative unfolding.

So, the question is, are these intuitions true, or are they just some sort of delusion or illusion? This is not just some trivial question because it has a profound existential impact. Some metaphysical systems like materialism (physicalism) reject those intuitions. This is a very grim position to take so many proponents try to counter that grimness with all sorts of semantic games and equivocations to avoid the psychological rebellion caused by those views. If viewed critically, they don’t work.

If, however, those intuitions can be affirmed, then the issue for a metaphysical formulation (in this case a theology) is how might those affirmations be justified?

Fundamental Assertions:

The Divine Life Communion theology (TDLC) affirms the key intuitions that people have.

- Yes, there is ultimate meaning and purpose

- Yes, there are objective values

- Yes, there is free will (could have done otherwise)

- Yes, ultimate reality can be related to (personally)

If those are to be affirmed, then how can it be done in a reasonable way? This is a complex question because it requires adopting a certain methodology and tapping into the full range of resources available. I cover this in detail in the “Developing a Theology” essay so I won’t go into it here. Suffice it to say that it requires features of being systematic and a few others:

- Logically sound (this means following the rules of logic)

- Coherent (makes sense, nothing obscure)

- Consistent (no self-contradictions)

- Rigorous (details matter)

- Complete (doesn’t leave out anything pertinent)

- Elegant (no contrivances to overcome a problem)

- Be science-friendly

Also, use of all available revelatory resources:

- Religious intuition

- The wisdom of the ages

- Religious traditions

- Science

- Philosophy

- Culture

- Art

- Moral sensibilities

So, with all that as the basis, here are the fundamental assertions of TDLC theology that seem to be necessary to affirm those fundamental intuitions:

♦ Reality is Constituted Intentionally

This is an essential assertion for affirming the intuitions. Without it, none of them can be affirmed without the addition of magic or supernaturalism. What I mean by “constituted” is how this reality comes to be and proceeds. If reality is constituted non-intentionally then we end up with an autonomic reality. This includes everything, including human beings. Things just happen with no purpose or freedom. In the non-intentional worldview, reality is constituted by laws and chance. This is the predominant (though not necessarily warranted) interpretation, often inferred from empirical investigations (science). TDLC says there are no laws or chance. Every event in this reality occurs freely and intentionally. This includes both the regularities and novelties we see. Some detailed essays on this are: The Theological Implications of Quantum Mechanics and How is Reality Constituted?.

This, of course, implies there is a constituting agent which I call God who intentionally and freely determines every event. So, there is a meaning and purpose for everything that happens. Now, an immediate reaction to this assertion could be that this rules out free will for humans and other creatures. This reaction would be warranted if no other assertions are made. I’ll get to those other assertions shortly.

♦ This Reality is the Creation of the Divine Mind

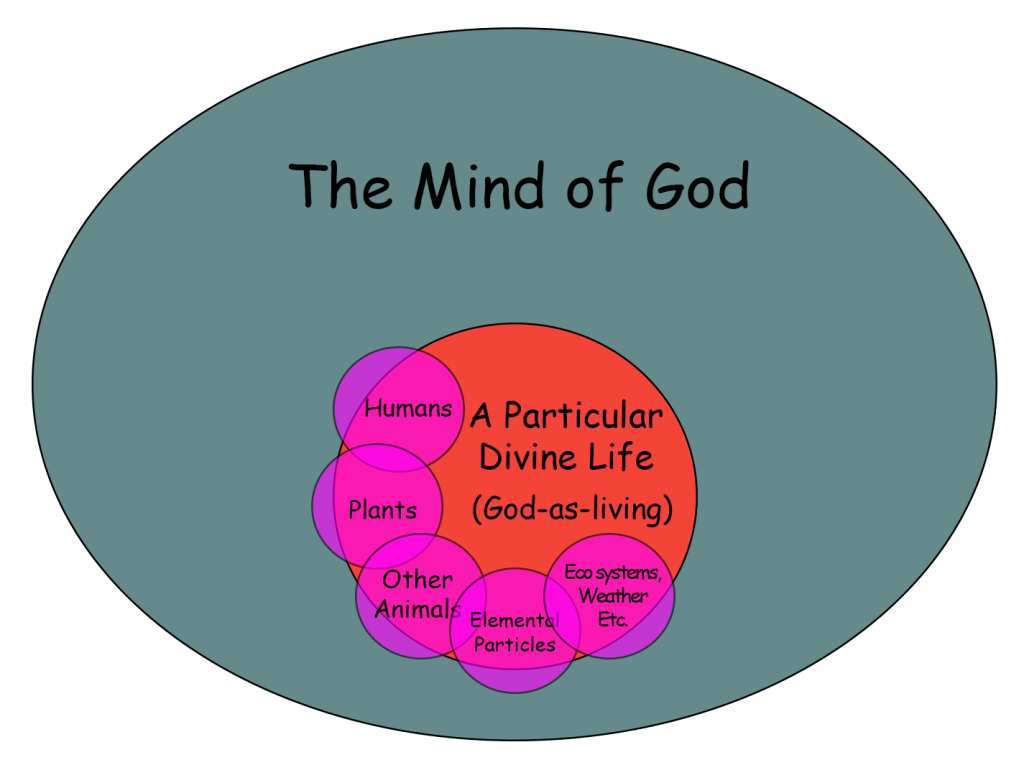

If reality is constituted freely and intentionally, then the most straightforward and parsimonious way that can happen is that it is the product of Mind — the Mind of God. I call this a Divine Idealism. A metaphor I often use to illustrate this is Author/Story. The author creates a narrative in her mind. She creates the world, the environment, settings, characters, and events intentionally according to the purpose of the narrative. The key thing here is that everything is in her one mind. Another advantage of this assertion is that it addresses the question of consciousness. There is no dualism or mind/body problem because everything is mental. Although the complete ontology of this theology requires considerable explanation, here are a couple Venn diagram metaphors for this. I cover this ontology in detail here.

♦ God Lives — An Aspect Monism

Often in theologies, a sharp distinction or dualism is drawn between God and this reality. This creates all sorts of problems for theology and affirming our intuitions. Those are well-known in theology so I won’t go into them here. So, what does it mean that God lives? It means that God chose to take on finite being. This has been asserted throughout the history of religious thought, even dating back to one of the earliest texts (circa 2nd millennium BCE), the Epic of Gilgamesh where Gilgamesh was 2/3 god and 1/3 man. It shows up with the avatars in Hinduism, Greek mythology, and the incarnation story in Christianity. How does this happen? A common way to characterize this is with the Greek term “kenosis” — the act of self-emptying. The kenosis of God is the intentional act of taking on constraints — going from the infinite to the finite. I use the term “life” for this constrained being. You’ll notice in the Venn diagrams these lives include everything from fundamental particles (or fields) all the way to sentient beings. Each “life” has certain constraints and limitations within which they (God-as-living) live.

I call this part of the ontology an aspect monism. This addresses the perennial question of the One and the Many. There is only the One (monism) but there are real distinctions within the One. These distinctions are aspects of the One. Now the term “aspect” has several different meanings. First, it represents a part of something. And second, it represents a perspective or type of being.

As an analogy, here we can think of the different aspects of our own selves. We are complex creatures with many different aspects. There are various parts to us. We have a brain, hands, organs, eyes, ears, etc. Each is an aspect of the self — a part and also a perspective. Each has its own purpose and striving but they all occur within a unified self (the One).

This assertion has far-reaching implications. God chose to live finite lives — take on constrained being. However, since all individual lives (God-as-living) are parts (aspects) of God-in-totality, they also have an individual, finite share of divine freedom, divine values, divine purpose, divine meaning, and divine consciousness. The importance of this cannot be overstated for affirming those intuitions I mentioned. It means there is a source for why those intuitions can be affirmed. There is a partnership between God-as-transcendent and God-as-living in how reality gets constituted. God-as-transcendent honors the freedom of God-as-living. I talk about a way to think about this in the essay: Divine Action.

This has far-reaching implications for many issues like prayer, free will, morality, the problem of evil, our assessment of the world, etc. You can check out the other essays in the left menu for these.

♦ There is a Communion of All Things

It can be tempting to think of ourselves in relative isolation. We know our actions do have an effect on others and the world but only in some localized way. For instance, when we talk to someone or take some action in the world, it does have a proximate effect but is not thought to be that far-reaching. With an aspect monism and divine idealism, this is not true. Every thought and action changes the Mind of God. Since everything is interconnected within the Mind of God, even the smallest change affects everything else. It changes not only what happens in the present, but also what can potentially happen in the future. In other words, there is a Communion of all things within the Mind of God. This means our view of ourselves and the cosmos should be holistic.

Now, this might sound reasonable in an abstract way, but is it real? Intuitions and abstract concepts can be a starting point for discovering “the real”, but for them to have verisimilitude (the appearance of being true), they should be tested, if possible. One way they can be tested is to put them into practice in everyday life. If they seem to work, that lends credence to their truthfulness. Another way is to look to empirical investigations as in science. So what do we know from science that might bolster the assertion of communion? I won’t go into detail here because I have an entire essay on “The Theological Implications of Quantum Mechanics” where I show how quantum mechanics does, in fact, affirm non-local effects. Everything in the cosmos is connected and affects everything else.

The System

The question/answer process is inherently interactive and non-linear. As questions are asked and answers offered there is a constant feedback loop where all the questions must find adequate answers. If a proposed answer for a certain set of questions doesn’t seem to work well for other questions, then more work has to be done. This may mean slight modifications will suffice or it can mean a major overhaul is in order. This also means there is an expansion of interest beyond the initial domain. What are the downstream implications of those foundations? What does it mean for how to live? What about prayer? What is our relationship to ultimate reality? How should we think about problems in life?

Metaphysical formulations can offer a framework and orientation for a worldview but what is ultimately important is how we live. This should never be forgotten. Otherwise, all the effort in formulating a system is just some sort of intellectual game, and not relevant beyond that.

The Divine Life Communion theology is non-traditional. It is not tied to any religious tradition, religious text, or scripture. As such, there is no objective authoritative basis for it. Instead, any and all possible revelatory resources can be drawn upon and assessed for their truth value. Now, an objection to this approach could be that it leads to rampant unbridled speculation and ultimately a metaphysical relativism. That would be the case if there was no “test” for veracity. However, I think there is but it is not as definitive as some would hope for. As stated above, one of the foundational assertions is that everything is an aspect in the life of God. This means that everything participates in the transcendent divine (God-as-transcendent). That participation means there is discernment available. If a particular formulation resonates with our transcendent divine depth, that lends credence to it. Here, a music metaphor could be helpful — consonance and dissonance. That which is consonant with our divine depth just seems right. That which is dissonant, begs for resolution. The process of seeking and finding resonance/consonance is a lifelong process. Things and situations change. Each new moment in life offers the opportunity to probe our divine depth and seek truth, love, beauty, and meaning for that situation.

Since there is no objective authority, this also means a healthy dose of humility is in order. We are fallible, finite creatures so we can be mistaken or partially mistaken. However, even with that, we can take a stand in what I call a faithing-falliblism and act.

While there is no objective authority for the theological system offered on this website, the question is, “is it compelling?” or at least somewhat compelling. This is an individual assessment and is as it should be. Worldviews are ultimately personal. If the theology offered here is, at least, somewhat compelling and informs a helpful way to think about oneself and live, so be it. If it is found lacking, so be that as well. The search for a meaningful life and spiritual fulfillment can take many paths.