An ontology is the foundation for a theology or religious philosophy. It sets the stage for what will follow and also circumscribes how various issues can take their shape. In this essay, I’ll describe the ontology I chose and employ for the systematic theology — an aspect monism and divine idealism.

Rationale and Method

Ontology is often defined as a branch of metaphysics dealing with the nature of being. It attempts to characterize what is, and the relationships within being. Before I get into a discussion on ontology, let me explain the rationale and method I employed for choosing the ontology I’ll suggest. It’s not that there aren’t plenty of ontologies out there to choose from. There has been thinking about metaphysics for millennia. Ontologies show up in both religious and non-religious systems. If we are interested in the truth of things, then the question is how to choose among all these for something that can be, at least, tentatively accepted.

Traditional religious systems like Christianity, Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and the like offer their own take on ontology and are often very different from one another. Some religious traditions claim their ontology is true because of a divinely inspired text or scripture. We even get literalist versions of this where divine revelation is considered to be direct from the divine like a dictation of sorts. In other words, it is not mediated by our perceptional abilities, cognitive powers, or personal biases. I reject this unmediated approach. I think that revelation occurs but it is mediated by our finite being with its own biases, desires, and inclinations. If this is the case, where does that leave us if we are looking for the truth? If there is no definitive revelatory resource then what criteria can we use to evaluate the various systems or components of ontology? I cover this in detail in my essay on developing a systematic theology from “scratch” but here I’ll just list them.

- Better address problems/issues

- Verisimilitude (appears to be true)

- Be reasonable

- Take seriously religious experience/intuitions

- Be systematic

- Be science-friendly

- Be world-affirming

Now, in order to be systematic, all these criteria need to be met by the system. However, what drives the whole process is to see if better answers can be found for the problems/issues that concern us existentially. Those problems/issues/questions are:

- Meaning and purpose

- The problem of evil

- Teleology (divine activity and science)

- Worldview assessment (good/bad)

- Free will

- Morality

- Prayer

- Consciousness (subjective experience)

At one point in my life many years ago I realized that Christian theology, in many ways, was not compelling to me anymore. I saw fundamental problems with the theology. However, since I still believed in God, I searched other religious systems to see if I could find something I could accept. While many of them offered things I could accept, they still had problematic areas for me. Now, just because there are problems within a theology or metaphysic doesn’t mean it should be rejected out of hand. Maybe those problems could be “fixed” within the system. This task to “fix” or make a theology more compelling for the current sensibilities has been going on for millennia. But what if those problems stem from fundamental principles or tenets? If that is the case, then no fix is possible. That’s what I found in my search. The major religious traditions were formed millennia ago and because of that, they adopted concepts and sensibilities about reality that don’t seem, to me, appropriate now. Some of those include:

- World rejection

- Supernaturalism

- Dualistic tendencies

- Inadequate answers to the problem of evil, free will, consciousness, prayer, etc.

- The lack of science-friendliness

Now to be fair, these traditions at inception didn’t have the knowledge or concepts about reality that we have now. They were developed within the thinking culture of the time. That is not to say that there was no wisdom or metaphysical revelation inherent in them. On the contrary. I think there clearly were but with each age, new information and experience challenge what came before. So, if these religious traditions don’t seem compelling to some people today then perhaps is it appropriate to revisit theology and religious philosophy to see if there can be better answers offered.

The reason I say “better answers” is two-fold. First, metaphysics (beyond or underlying the physics) is always underdetermined. There is only so far we can go “down the rabbit hole” with empirical investigations. If we wish to go beyond that point we must indulge in inferences and speculations. How those speculations take their shape varies. They can range from wild undisciplined speculations to those that are more rigorous — holding to higher standards of logic, reasonability, and empirical friendliness. For the criterion of “better answers” I think a more rigorous, systematic approach may be more compelling to many.

So, if the criteria that I mentioned are employed, this can offer a way to discern whether or not better answers are available. While many of those criteria appeal to our sense of logic and science-friendliness, I think there is a definitive criterion that is an ultimately determinative factor. This is where a presupposition comes in. That presupposition is that there is a divine presence in everything. If that is the case, then when we are confronted with a formulation regarding God and God’s relationship with this reality, the formulation may ring true or not. Here I’ll use the metaphor of resonance. When two pitches of different musical instruments are in tune, and one instrument is excited (plucked in the case of a stringed instrument) the other instrument will resonate with it. They agree with each other.

Now, in regard to metaphysics, this is where things get tricky. We are finite creatures with many limitations, competing motivations, and desires. There can be multiple resonances occurring. On the one hand, there may be a resonance with our desires, motivations, and goals as finite, contingent creatures but there also may be a resonance with the divine depth within. We all experience competing resonances as we face momentous decisions. This is the essence of ambiguity as finite beings.

So, since we are individuals with our own particular biases, I think it is important to view problems/issues/questions in a broader sense. Are there metaphysical problems that show up consistently throughout cultures and time? If there are, that should lend credence that something is wrong with a metaphysical component. To use a music metaphor, there is a dissonance. Something seems wrong.

Now, that dissonance can be the result of many things. It can be dissonant with our own experience. It can be dissonant with reasoning or empirical suggestions. It can come from a myriad of many sources.

I do believe that the divine is within everything so the process of evaluating an ontology is about finding a resonance between the divine within and the whole gamut of our experiences, knowledge, reasoning, and intuitions. Every resource can and should be brought to bear in the evaluation. This includes things like religious experience, empirical data (science), reasoning, emotion, art, music, culture, philosophy, psychology, and anything else that is available. Since we are talking about metaphysics, this process will always be underdetermined so a judgment call is necessary. Accordingly, any proposed ontology should be met with a healthy dose of humility. In the final analysis, whether or not an ontology is true should consider the “marketplace” of ideas and how they are received. This may help attenuate personal presuppositions and biases. Now, this is always an evolving process as new knowledge and experiences arise within cultures and groups. However, there is a reason that among the myriad of religious systems offered throughout the ages certain ones, namely the traditions, became prominent. There are many reasons for this that aren’t about revelation like group interests, politics, social dynamics, control, and the like. Still, I think the main reason is that there were elements in them that did offer a glimpse of the divine. Those elements resonated with the divine within and, even if flawed, were accepted by many.

While I do think that there is a wealth of truth and insight to be found in the traditional religious systems, as I mentioned earlier, I also think there are fundamental flaws within them that can’t be just tweaked away. It’s not that this hasn’t been tried. The history of theology and religious philosophy is full of attempts to “fix” the persistent perceived problems within them. The problem with this, in many cases, is that if problematic elements arise because they stem from fundamental tenets then any “solutions” will necessarily be in the form of contrivances or inelegance. I think that is the situation we find ourselves in today. So, what I’ll offer here is an attempt to formulate an ontology “outside” the traditions while still drawing from them and any other resources available. Like any theology or religious philosophy, it can have weaknesses or areas that may still be problematic. That should be affirmed. Still, I think new attempts to formulate an ontology and the subsequence concepts and ideas that follow are necessary because they do affect what happens in the world and whether or not they promote the good.

Ontology

In any theology or religious system, ontology is a cornerstone for what will follow. In the essay on developing a systematic theology, again I said that the key element in the approach/method was to find an ontology that offered better answers to certain existential issues than have been offered in the major religious systems. The main issues/questions are:

- Meaning and purpose

- The problem of evil

- Teleology (divine activity and science)

- Worldview assessment (good/bad)

- Free will

- Morality

- Prayer

- Consciousness (subjective experience)

In this essay, I’ll describe the ontology that I think does offer better answers for all these issues. First, a bit of background on ontology. All religious systems attempt to characterize the nature of reality. This is a vast subject but here I want to focus on a few areas.

Distinctions — The One and the Many

One of the tasks of theological ontology is to explore what difference there may be between God and this reality. The question is how to talk about this and what terms to use. Often terms like dualism, monism, and nondual are used but these all have nuances that can make it difficult to understand what is meant. So, here I’m going to use the term “distinction”. It’s a term that, I think, we can easily relate to.

We intuitively understand that we are somehow distinct but also part of something more than ourselves. How are we to understand what that distinction means in metaphysics? For millennia this issue could be phrased as the question of “the One and the Many”. It may have been first dealt with in-depth by philosophers in the Indus Valley (circa 800 BCE) of what we now know as India and also in Greece. There, early philosophers seemed to diverge into two schools, dualism and monism. Another term that is often used in Eastern religions is “nondual”. It can have different connotations but for the task at hand, I’ll use the term monism. For the dualists, the ontological distinction is stark and fundamental. The dualists in religion claimed that there are two starkly distinct ontological realms, the realm of God or some form of ultimate reality and this reality. The monists claimed that there is only the One and we are parts of that One. There may be distinctions within the One but they are not ontological. Of course, that needs to be unpacked which is what I’ll try to do.

This ontological debate has continued throughout history with various formulations being offered. While in the East, monism (or nondual) took a stronger hold in the religions of Buddhism and Hinduism, in the West, with monotheism becoming pervasive, a dualistic view — a strong distinction between God and the world became dominant. This resulted in what we now know as the classic theism of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. This is not to say that there were no monistic trends in Western religion. Every age has had reactions to dualism in theism but dualistic tendencies still seem to remain prevalent. However, more monistic approaches have also become available. Particularly among professional theologians, there is a resurgence in monistic thought that is called panentheism. Panentheism says that the world is “in” God but God is also more than the world. While there are forms of panentheism that, in my view, still have dualistic tendencies (as in process theism) there are other strains that assert the oneness of reality. I believe a monistic form of panentheism fits experience very well and solves many problems in theology. The question that arises is how to characterize a monistic system.

In theology, distinctions matter greatly because they speak to many of the existential issues I mentioned. They shape the answers given to those issues. I talk about this in many essays like on the problem of evil and how reality is constituted.

The idea of wholeness with the One and the Many can be particularly difficult for those in the West because they do not have a history of nondualism in their culture as there is in the East. To be sure, the great Western mystics and some theologians are part of this history but for the most part, I think, their sentiment has had less impact on Western culture perhaps because of the emphasis on rationality and the skepticism in a science-informed culture. That, however, has not deterred theologians and philosophers from grappling with the issue. These thinkers have opted for at least two common approaches. One is to use philosophic language and the other is to draw on metaphor. I think both are helpful. Now, there has been no shortage of metaphors to describe how a distinction can be made between the One and Many. One of the more popular ones in panentheism is that “the world is the body of God”. This metaphor is apt because humans can all relate to having many parts, cells, organs, the brain, etc. that are distinctions but also part of the whole. I do, however, believe there are weaknesses to this metaphor. While the intent of the metaphor to include God in the world is valid, I also think the metaphor can be problematic. In some cases, there is still a strong difference/distinction between God and the world. Another problem is that it seems to still affirm the notion that there are laws of nature that operate autonomously. This “body” of God is governed by these laws so divine action must be in some form of supernaturalism. I also don’t think this ontological metaphor addresses well issues like free will, consciousness, teleology, divine action, and the problem of evil.

The question is how to talk about distinctions within the One. I use two phrases to describe an ontology that I think better addresses these existential issues. They are an aspect monism and a divine idealism.

An Aspect Monism

Often in theological formulations, there is an inherent, stark distinction made between God and the world. This is prominently found in classic theism where God is unchanging and impassive. Since this reality is finite and contingent, there is a strong ontological difference between God and the world.

An aspect is a part of something. It is a distinction but only within the One — thus the monism. I think “aspect” is an apt term because it can draw some distinction without creating a dualism or stark ontological distinction. I also think people can relate to the term because we all recognize that we have distinct aspects to ourselves while remaining a unity.

Here’s an extremely important consequence of an aspect monism. Since there is this finite reality as an aspect of God, aspects in this reality literally are a part of God. There is no stark ontological divide. There is no ontology with dualistic tendencies. Now, while this reality is an aspect of God it is not the only one. As in panentheism, God also has a transcendent aspect. This is often called the unknowable, abysmal aspect that is the “more” in panentheism.

Another important point is that aspects aren’t to be thought of in isolation. Aspects combine to create more complex aspects. Here again, you can think of your own body. Each organ or system has certain distinct features and purposes but they don’t just do what they do in isolation. Parts affect each other and even change how the different parts function. Or think about how this reality is constituted by the elemental particles or quantum fields, each an aspect of the whole. So, aspects may also reference complex systems. While there are distinctions, there are no absolute boundaries. This is why the TDLC theology is called a Communion. Everything is connected and integrated. Since there is this constant integration and interaction between the parts, there is really a blurry line when talking about distinctions within the whole. Distinctions can be characterized but only in relation to the whole. Here we can think about the connectedness within families, societies, and even the planet and cosmos where the parts (aspects) affect all the others. Now, the next question could be how to characterize what context this complex system of aspects occurs in. Here I think a divine idealism is apt which I’ll talk about shortly.

There are also some explanatory advantages to an aspect monism. Dualistic systems have difficulty explaining how free will could work. This is also true for the issue of consciousness (subjective experience). However, with an aspect monism, both these attributes can find their source as aspects participating in God. If we are an aspect of God then we can share, in a limited way, in God’s ultimate freedom and Mind.

Another important advantage of an aspect monism for theology is that there is no divide to be crossed to commune with God. There is a seamless interrelationship between the aspects of God. Instead of a divide, there is an infinite depth to all of reality. Religions often divide reality into the sacred and the mundane or profane. We can think, instead, of the sacred as that which dwells in all things and seeks to embrace its divine depth. An aspect monism also dispels the typical conflict between religion and science. If reality is monistic there is no need to talk about “interventions” of God in this realm. Instead, God’s activity is intrinsic to reality in God’s living aspect. Divine action is not something imposed on the world from the outside but rather the ubiquitous activity of a living God in every moment of life. From the standpoint of a personal sense of self and action, if we are aspects of God then we are not fallen creatures but participants (aspects) in the Divine Life with all its challenges and opportunities.

Divine Idealism

There are many types of metaphysical idealism. Essentially, however, it means that this reality is fundamentally mind. How that is fleshed out can vary quite a bit. In the form of divine idealism I’ll be talking about the ontology says that this reality is part of the Divine Mind. Now, it is important to remember that when we are trying to characterize God, the terms we use are necessarily metaphorical based on our own language and concepts. So, when I say “Divine Mind” I’m not suggesting that God has a mind literally just like ours. What I’m saying is that since we have minds it is reasonable to suggest some metaphorical semblance in God as well. Metaphors aren’t intended to be taken literally but hopefully, they point to some deep truth. After all, all we have to work with in theology and metaphysics are our own concepts. So, I’ll offer several metaphors to illustrate what this divine idealism entails.

I’ll use a couple of phrases from here on to talk about the distinctions. They are God-as-transcendent and God-as-living. Like in panentheism God is both transcendent and immanent.

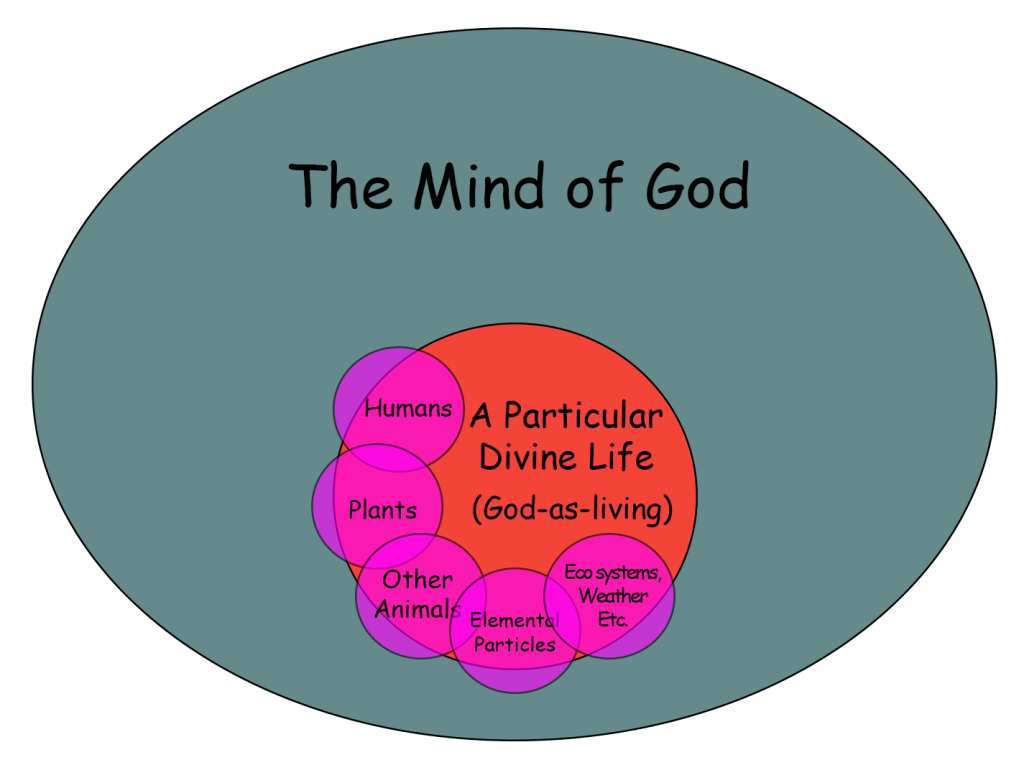

To illustrate this here are a couple of Venn chart metaphors. Here is a full explanation of these Venn diagrams.

To illustrate this further, here’s another metaphor from something that might be familiar. The metaphor is Author/Story. If we think about an author writing a story what we have is the one mind of the author but within her mind, there is a part we call a narrative. The author imagines a general narrative for the story. She creates characters, environments, places, and events. Now, remember everything is within the author’s mind. Then in her mind, she “plays” each role. Each role may be very different but the author lives that role according to the role’s attributes, disposition, strengths, and limitations. For the general setting, the author plays the role of the setting and with it the places and environments. This setting could be either realistic or fanciful. Then the author plays the role of the characters in her mind, trying to honor who they are and what they might do. These characters could be heroes, villains, ordinary people, or any other character type. It’s important to note that the author “becomes” that character in order to make it realistic. That role may be very different from the author, herself but she adopts that role’s characteristics nonetheless.

Now, the author has a general sense of the narrative but as it proceeds the author must adapt to what has happened as well as where the author wishes the story to go. Sometimes the narrative may take a turn that even surprises the author. I have heard (and experienced myself) authors attest to the fact that sometimes the characters surprise the author in what they do. “Where did that come from?” So, the characters and the environment seem to have a life of their own. This would be an analogy for free will. In this metaphor, the mind is One, the mind of God, but the characters in the story that God creates share in God’s mind and some of its attributes.

It’s important here to emphasize the faithfulness of God in taking on each aspect or role. Not just anything goes. There are constraints that limit what is possible. So, for instance, God, in living the role of the environment faithfully follows the intentional God-given constraints that the environment conforms to. Those constraints make life possible. This includes both the stability and novelty that is inherent. There are regularities followed faithfully but there is also novelty being actualized as well. This has been characterized in science as the statistical nature of how reality is constituted. So, each aspect of the Divine Life lives that life within this boundedness.

Here are links to two more metaphors to illustrate the ontology: Actor/Role, and Role Play Games.

Consequences:

The Divine Life — Constrained Being

What is life? This is a controversial question. Does life require metabolism, replication, complexity, etc? From a theological perspective, however, I would like to focus on a broad feature — constrained being. However life may be defined, it occurs within constraints. There is a structure to the universe and it is within that structure that beings exist. There are regularities at work that constrain what can happen. There is also novelty inherent as described by quantum mechanics, but that novelty is also constrained. The Born rule in quantum mechanics is one way it is characterized. Then we have what has been called the “fine-tuning” of many parameters of the universe that are needed for life to exist. The bottom line is that these constraints make life, as we know it, possible. They allow for dynamic processes to occur that support things like energy flow, information transfer, and stability as well as change. To live is to exist but still be constrained in certain ways. So based on this concept (constrained being), all entities in this reality are living — elemental particles, molecules, rocks, plants, animals, human beings, ecosystems, the cosmos, etc. I think it’s appropriate to include complex systems like the weather as living because individual entities do not live in isolation. They interact and combine to make up other forms of life. For instance, in our own bodies, there are molecules, chemicals, cells, organs, and even bacteria, and viruses (some beneficial, some not). If we extend this further, we can think of societies of individuals, the planet itself, and even the cosmos. I hope this isn’t too obscure but some term (life) is needed to talk about what is distinct about this reality within God. In this form of divine idealism, everything is living and part of the Divine Life. There is only the One (God) but there is an aspect of God that lives.

The term “Life”, when used with “Divine”, is also a metaphor, but I think it is theologically apt because we as human beings have a deep sense of what that means. In an aspect monism this means that God chose to live — to participate in finite, constrained being. Throughout history, there have been examples similar to this idea in metaphysical and religious literature. In Christianity, we have the incarnation. In Hinduism, the avatars. Also in Greek mythology, God takes on human form. In these cases, God incarnates or lives a life in specific individuals. In the Divine Life Communion theology with its aspect monism, everything in the universe is an aspect of the Divine Life. Everything is an incarnation.

So how do we make distinctions within the One? As I said, I use the phrases God-as-transcendent and God-as-living to make this distinction. It is not an ontological distinction but rather a distinction within the One.

God-as-transcendent

In most common concepts of God, God is ultimately free and unconstrained by anything. This is in contrast to finite constrained being. While there is a finite universe, God transcends that finitude infinitely. This transcendence is often called the abysmal character of God that is “more” than this reality.

While this reality is finite, God-as-transcendent has been called “the ground” of everything. It is from this ground that everything proceeds. Accordingly, there is a transcendent basis for what we see and feel intuitively. This finite reality is derivative from the transcendent. Things like finite meaning, finite freedom, finite value(morality), finite consciousness, finite purpose, etc. are all a finite share of the ultimate attributes of God-as-transcendent. The qualifier of “finite” means that while there is a share of the transcendent within the finite, there are also limitations inherent in finite being. So, there is uncertainty and ambiguity. This leads to a discussion of what God living constrained finite being means.

God-as-living

In an aspect monism, while God is transcendent, there is also an aspect of God that takes on finite being that we call this reality. In other words, God chose to live. If we understand life as constrained being then there is a Divine Life. Within the totality of the Divine Life, there are the distinct lives I talked about earlier. So, God lives each of those lives — thus the term “as”.

If there are constraints within God, they are intentionally self-imposed constraints. In the Greek language, this is called kenosis which means self-emptying. We see this sort of idea throughout the history of theological thinking. In Greek mythology, gods or goddesses take on human form. In Christianity, it is found in the incarnation stories. In Hinduism there are avatars.

This has far-reaching consequences. If God lives each life faithful to the constraints of that life, then that has a profound effect on things like the problem of evil, divine action, prayer, moral sensibilities, etc. I cover those things in other essays but suffice it to say here that using the term “as” means that God accepts living many roles that may actually conflict with what God-as-transcendent would wish for this world. Why would this be the case? I think it is the case because each life, no matter how some actions may be contrary to God-as-transcendent’s hope for this world also presents unique opportunities for what we consider the most laudable features to emerge. Those include things like love, courage, resolve, selflessness, vitality, faith in the face of doubt, and so on. Here’s an essay where I suggest what the divine goals may be.

The Communion

Another important implication of this ontology is that since everything is within the One then everything is interrelational. While we are distinct individuals, there is no sharp line to be drawn between us and everything else. Everything affects everything else. That should be obvious as an individual’s thoughts and actions are not just self-contained but reach out from the individual to friends, family, community, the environment, and the world as a whole.

The term “communion” has various meanings but essentially it means a sharing and participation among individuals. There is no isolation because there is a constant intermingling of selves with each other and the whole. While this participation can come in the form of interactions via touch, conversation, sight, and so on, it is deeper than that. Since everything is part of God’s life, everything is in an ontology union — both with God-as-transcendent and God-as-living. As life proceeds, God-as-transcendent is changed and new possibilities arise. So, God-as-transcendent takes all this into consideration according to God’s divine purposes. This means that decisions made in this reality are not just localized but have a profound effect on what is possible for the future. It is the entire communion that shapes the direction and what is possible for the future.

Being in a communion means you are not alone. Your trials and joys are not just yours but those of everything else within God. It also means that what you do is important. No matter your situation in life, how you act and relate means something beyond that situation. The Divine Life is a communion of all things each with its own part to play in the grand narrative of this life. While we are individuals with our own lives, we are also important to how this grand divine narrative plays out. Each act of kindness and love contributes to what follows and the direction it takes.

Better Answers?

A legitimate question would be, “why should this ontology be accepted or at least entertained?” That’s a fair question but can’t be addressed in just a few paragraphs. The entire system comes to bear on this. I talk about this in various essays and blog posts throughout the website. My approach has been to see if an ontology can offer better answers to all the existential issues and questions we face. Evaluating that involves the full gamut of experiences, knowledge, and understanding. This includes cognition, emotion (valuations), reasoning, knowledge, and particularly a person’s religious sense. I say religious sense because I believe there is a divine depth to everything and when some idea that is offered resonates with that divine depth it may be compelling or at least partially compelling.

Although I talk about the answers in depth in various essays and blogs, here I’ll try to give a glimpse of the answers and why I think they are better.

Meaning and purpose

Obviously, with God as the source of this world, there is an inherent meaning and purpose to it. God has reasons for creating this reality. What those are and how we should respond to them is the challenge of theology and living. As finite creatures, it’s not a simple straightforward task but trying to align this life with those purposes can offer meaning to our lives and enhance them.

The Problem of Evil

This is perhaps the most challenging issue for theism. I think it requires mitigating factors. First, in order for there to be life, there must be a certain structure to reality that will support it. That structure, however, can give rise to both the good and evil. One might think of this as a yin/yang — opposites that as they interact create the life we see. In order for there to be life, the potential for evil is a necessary component. No “dark”, no “light”.

Second, who suffers?. In an aspect monism, it is literally God who suffers as each aspect. God does not “stand from afar” and watch the evil and suffering. God lives each life and experiences both the joys as well as the suffering. God also both creates the good and evil (faithfully adopting each role). The idea that God actually does the evil is hard to accept but if God is not some bystander then it is an inevitable conclusion. Ultimately God is responsible for the evil anyway but if God chose to live lives faithfully and experience the consequences, perhaps that is a mitigating factor. It means that there is something so important about living constrained being that God was willing to accept within God’s self the consequences.

Teleology (divine activity and science)

This is another difficult area for theology. Is God active in how this reality takes shape and evolves? If God is not just a passive observer, then how does God act in this world? This is where a divine idealism offers a radical alternative to the ubiquitous presupposition that reality is constituted nonintentionally via necessity and chance (laws and quantum chance). Instead of this, a divine idealism says that every event in the universe is intentional. There are intentional regularities that science tries to characterize and there is intentional novelty as well, where quantum events are seen as an intentional choice in the Divine Mind between possible actualities. Accordingly, there is no supernaturalism (interventionism) because there is nothing to interfere with. Both regularities and novelties are intentional. Here’s an essay on divine action.

Worldview assessment (good/bad)

Since in an aspect monism and divine idealism there is no ontological divide, this means that reality is exactly as God has planned. God takes on finite life and lives each life according to the purposes God has in mind. There is no fallenness to this creation. Accordingly, this world should be affirmed and not seen as fundamentally flawed and needing a “fix”. Certainly, there are problems to be aggressively addressed but these problems do not reflect a fundamental flaw with this reality but rather the meaning that life has to offer where the good is strived for even amidst the challenges of finite being.

Free will

Since God is ultimately free and everything is an aspect of the Divine Mind, this means that God’s ultimate freedom is shared with each aspect within the constraints inherent in each life. Here’s a link to an essay on this.

Morality

There is a divine meaning and purpose to this Divine Life. However, since this is finite life there are competing goals at work. God-as-transcendent has certain hopes for how this reality takes shape. I think those hopes include the creation of love, beauty, and meaning. But since there is also a finite freedom in play those hopes may or may not be chosen. There are moral choices to be made in every moment of life. Are the choices made in line with what God would like for this reality or not? Since we are finite creatures with limited knowledge that is the moral challenge with each decision.

Prayer

If God is active in the world then the question is whether or not we can influence how God constitutes reality? Prayers of supplication represent an attempt to ask God to actualize reality according to the wishes of the adherent. Since here we are not talking about a request for supernatural intervention, every prayer of supplication should honor God’s commitment to the ongoing creation of regularities and novelties that make life possible. Accordingly, prayers of supplication shouldn’t seek a disruption of that commitment but rather a hope that within that commitment God can shape reality toward some noble and faithful request.

Consciousness (subjective experience)

Subjective experience has long been seen to be problematic for a putative materialistic scientific worldview. The question is how can subjective experience be explained in a materialistic scheme? While this question has been around for millennia, there has recently been a resurgence of various models to address this problem. In a divine idealism where everything is mental, there is no ontological (mind/body) problem to be resolved because reality is constituted mentally in the Mind of God. Accordingly, subjective experience is not some foreign phenomenon to be explained but rather an inherent feature of mind.

Conclusion

Now obviously, I think this ontology does offer better answers and it resonates with me. But that’s just me. I have my own biases and inclinations. Others have theirs as well and that is as it should be. The Divine Life is complex with many lives, each with its own situation and sensibilities. I think we are at a moment in history where a fresh look at theology is possible and needed. Accordingly, I hope many attempts will be made to take that fresh look for something that is relevant and meaningful.

I don’t think theology or metaphysics is just some puzzle to be solved. It can have a direct bearing on the way we think about ourselves, act, and relate to the divine. It can shape our sense of self and our place in the universe. I believe God has a purpose in mind for this reality and when we align ourselves with that purpose we tap into our most profound self and find a deep meaning that cannot be found elsewhere. Now, we may experience this fragmentarily but it nonetheless has a powerful impact on us and can motivate us to further probe our divine depth both for ourselves, others, and our world.

Metaphysics is speculative and underdetermined. It relies on inferences and intuitions. Whether a particular system seems compelling or not ultimately ends up being a personal judgment call. So be it.

SHARE THIS: